brusselLs

TRIBUNAL DOSSIER on Fallujah [PDF]

FLASHBACKS:

Fallujah 1920: A history lesson about the town they have

destroyed

It all started in

april 2003, after the US invasion....

Fallujah: the April 2004 Siege (Jo Wilding)

Dahr Jamail's reports of the April 2004 Siege

List of Iraqi civilians killed in Fallujah

in the assault on the city in April 2004

In memory of Fallujah (Inge Van

De Merlen, 24 June 2006)

About the use of White Phosphorous. Click here to read

more.

Recent news and

articles about fallujah

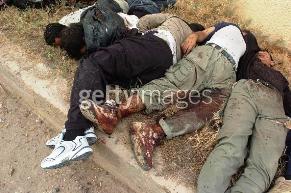

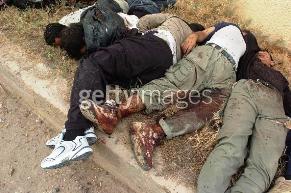

fotos: april 2003

JOHN PILGER:

I think the resistance in Iraq is

incredibly important for all of us. I think that we depend on the resistance to win, so that other countries

might not be attacked, so that our world in a sense becomes more secure. Now, I don't like resistances that

produce the kind of terrible civilian atrocities that this one has, but that is true for all resistances. And

this one is a resistance against a rapacious power, that if it is not stopped in Iraq will go on to North

Korea where Mr. Cheney and others are just chomping at the bit to have a crack at that country. So, what the

outcome of this resistance is, is terribly important for the rest of the world. I think if the United States'

military machine and the Bush administration can suffer a defeat in Iraq, they could be stopped.

(Wednesday,

December 31st, 2003)

A

Bridge Across Tears For Iraq

A Statement of Solidarity in Suffering

To the People of the World who profit from our tears

To the People of the World who profit from our tears

To the People of the World who care not of our tears

To the People of the World who know not of our tears

To the People of the World who live also with our tears

We speak to you, in whispers and in screams; in despair and in hope; in defeat and in struggle; to reclaim

our humanity.

With the violated people of Iraq, we stand in solidarity, our arms joined in this bridge across tears.

We learn everyday of the killing, plunder, destruction and humiliation that takes place in Iraq.

We have heard the tired justifications of Power many times over - security, freedom, democracy,

reconstruction - these are words that are not alien to us; they haunt us everyday as we tread upon our

earths.

100,000 lives, of children, women and men, in Iraq have been the latest price to be paid for the betterment

of civilisation.

Innocence is no protection. We know.

For each one of the 100,000 lives sacrificed at the altar of Power, united in death rests the remains of

100,000 more of our sisters and brothers of many names upon that same altar.

The tanks, the bullets, the airstrikes, the depleted uranium, the torture, the collective punishments, these

that have been the weapons of vengeance against the people of Iraq, are all kin to the hunger, the

destitution, the 'structural adjustment programmes', the poisoned rivers and lands, the suffocating clouds of

'progress', the police truncheon, the barbed wires, that have been and are our scourge.

The tanks, the bullets, the airstrikes, the depleted uranium, the torture, the collective punishments, these

that have been the weapons of vengeance against the people of Iraq, are all kin to the hunger, the

destitution, the 'structural adjustment programmes', the poisoned rivers and lands, the suffocating clouds of

'progress', the police truncheon, the barbed wires, that have been and are our scourge.

We name all as violation.

As we shed our tears for our losses, our tears fall also on the lands of Iraq.

Though Power seeks to blind us with their lies, our eyes remain ablaze with the fire of life that we carry of

all our dead.

And we denounce Power with its many faces of violence.

For theirs is not a 'Security' in which we are secure.

Theirs is not a 'Freedom' in which we are free.

Theirs is not a 'Civilisation' in which we are dignified as humans.

Theirs is not a 'Civilisation' in which we are dignified as humans.

This we say as we build a Bridge Across Tears:

To Power:

We notify you that we, the peoples of the global south, stand together with the people of Iraq in resisting

your cruelty. Be aware.

We demand of the US-UK led 'Coalition' the cessation of violence against the people of Iraq, the withdrawal

of all the occupying forces from Iraqi lands, and the restoration of the will of the Iraqi people for genuine

self-determination.

We demand that those who call themselves leaders of nations act as leaders in halting the impunity of the

Occupation in Iraq by mobilising themselves against the US-UK led 'Coalition' in Iraq.

We demand of the United Nations immediate action to withdraw support for the on-going Occupation of Iraq, and

to initiate an international process of judgement against the illegal and criminal use of force against the

people of Iraq.

We affirm our common humanity in struggle, with the people of Iraq against the invading forces, and with

sisters and brothers everywhere against the invasions upon their lives, livelihoods and dignity.

We affirm our common humanity in struggle, with the people of Iraq against the invading forces, and with

sisters and brothers everywhere against the invasions upon their lives, livelihoods and dignity.

We pledge that ours is a common struggle for peace, justice and humanity.

To the People of the World,

We call on you to be a Bridge Across Tears so that Humanity may prevail over the cruelties of Power.

Jayan Nayar

Coordinator

Peoples' Law Programme

I Am Fallujah

I Am Fallujah

I am Fallujah.

Once before I endured the colonial arrogance

of another nation

upon my soil.

That was 87 years ago,

and with their superior weapons,

they, too, came to liberate us.

I cried out.

I warned them

that I would not endure

an uninvited presence.

The Empire thought

my people ignorant.

And now, under a different flag, you strike with the precision of deranged camel,

your weapons missing your stated target

again and again,

all the while knowing

your real target

is complete conquest.

You screamed when my people vented their rage upon one or two of your suited predators.

With false indignation, you summoned your weapons of mass destruction while truckloads of our dead rumbled

past your snipers to a lonely mass burial.

Sometimes you even shot at the drivers.

And when my people reported the downfall of another child, another family

in one of your precision strikes

you claimed they lied,

they exaggerated,

they falsified the facts.

Do they exaggerate today when a pall of ten thousand

misinformed soldiers enter their city

with homicidal rules of engagement?

Have you told your own people that those orders include

shooting surrendering citizens on sight?

And still you use the language of benevolence.

You promote the dubious presence of a sinister entity

to re-direct world attention

through your selective, rhetorical lens.

Zarqawi, Zarqawi, Zarqawi you chant

as you handsomely reward your media servants

for their silence.

Yet you dare not acknowledge that with each death,

you induce the birth of another fighter.

With each bomb,

the hatred of your colonial ambition grows.

And around the world, with every drop of blood you cause,

you feed reaction and backwardness the very food it needs

to sabotage the aspirations of the worlds people.

The true freedom from oppression you so cynically claim to champion.

To meet your ends, you consciously blur the distinction between terrorist and insurgent.

The terrorist is your ally, although you call him enemy.

The terrorist is the veil behind which your blood encrusted nails

attempt to gouge out the clear vision of humanity.

The terrorist is your very own Frankenstein monster

forged in the laboratories of your foreign policy.

The insurgent simply fights to be free - of you,

a searing resistance born from the fires of scorned dignity.

While your craven campaign

may momentarily subdue those who survive,

you shall neither defeat them, nor befriend them,

for the tincture of time

will barely soothe the memories

of such atrocities as yours.

I am Fallujah. I am all cities under imperialist siege.

We have fought you before.

We know what motivates you.

We know your eyes.

They reflect the barrels of black poison

that have drained you of decency.

And in your murderous pursuit of plundered profits,

you stand to condemn all of our children

to a lifetime of intellectual and emotional anguish.

Remember this: we did not invite you into our house.

When you claim the mantle of nobility,

know that it is in infamy your legacy will find its home.

Fallujah invaded by US forces on November 9th 2004

Jenny Campbell 12 Nov 2004 03:52 GMT

This poem was written a few days before the invasion began and updated it the day of

the invasion. May it circulate widely!

Freedom carol

Nedhal Abbas*

Ah

I'll say it again:

There are few things

On which we all agree;

Sooner or later

You'll be free.

Democracy is new for you

But never mind

We will teach you

Marines;

Move forward

Go on

This is what you trained for

You are the hunter

You are the predator

Freedom is beautiful

Do you hear?

Soldiers march,

On natives bodies

Battling a stench

They chant

Freedom is beautiful

By tanks

By warplanes,

Apache, Kiowa, marine cobra.

Smoke grenades

By Sniper shots

We'll end your demise

They deliver.

Wrapped in democracy,

Coloured in freedom,

Packages of

Un- named mutilated naked burned

Blown apart un-counted bodies

We receive

137,000

Men women and children

Mohamed, Ali, Omar, Jawad

Selma, Nadia, Fatima, Suhad

Hussein, Ahmed, Salam, Azad

Aysha, Amal, Maysoon, Nuhad

Faisal, Raad, Zaid, Widad

Nuha, Haifaa, Kifah, Souad

From a distance'

Chorus of freedom recite:

Ah

We'll say it again;

Can't you understand?

It's our mission

To put an end

To your demise.

Nedhal Abbas: Iraqi poet. She published her first book of poetry "Dreams of

invisible pleasures", in Arabic, in 1999.

This poem has been translated by Haifa Zangana. (first published on

http://www.idao.org/freedom-carol.html

)

Fallujah:

Shock and Awe

Ken

Coates, Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation.

It was on April 26th 1937 that the name of Guernica was

immortalised. A little town, home to 7000 people, Guernica was

the local market place for a cluster of hill villages. It

straddled a valley only ten kilometres from the sea, and thirty from Bilbao.

It was a cultural centre for the Basque country, with a hallowed oak tree upon which for centuries the

public power in Spain has been obliged recurrently to affirm an oath to respect the rights of the Basque

people.

April

26th was a Monday, market day. It went ahead peaceably, although the Civil War was raging thirty

kilometres away. The air raid was not announced (by an urgent

call from the Church bells) until half past four in the afternoon. Ten

minutes later Heinkels arrived, scattering their bombs across the town, and then machine gunning the streets.

Following the Heinkels came the Junkers. The German Air

Force was celebrating a major practice run. When the people ran

away, they, too, were machine-gunned. One thousand six hundred

and fifty-four people were killed, and eight hundred and eighty-nine were wounded.

The town centre was destroyed, and Europe received its first baptism of aerial bombardment on a modern

scale.

The shock reverberated far beyond the Basque country.

Spain was not a remote colony like Iraq, from which news could take an age to travel.

Within a week Picasso began his painting, his masterpiece which is at present installed in a special

gallery attached to the Prado. In preparation for this, he

feverishly prepared a desperately poignant series of sketches and cartoons, one of which we feature on our

cover. Picasso gave us a portrait of naked horror.

Europe was soon to learn the face of that horror at first hand. It

is said that when some German officers visited Picasso in his studio in occupied France, they said of

Guernica, drawings from which were hung in the room, “Did you do this?”

The master is said to have replied: “No, you did”.

But

it was not only the German Air Force which tore away at the fabric of European cities.

Coventry and London pale into insignificance when compared with Hamburg and Dresden.

It was an American soldier, Kurt Vonnegut, who was to create a memorial to Dresden, in his

extraordinary work Slaughterhouse Five. Slaughterhouses,

since, we have seen in profusion. Before the incineration of

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, there was the massive “conventional” air raid on Tokyo which killed many tens of

thousands of people. Then we lived through the Cold War, and the

nuclear arms race, until we entered, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, into the age of Full Spectrum

Dominance from Washington. Now the centre of that domination

sits in Iraq, and for the time being the carnage radiates out from the city of Falluja.

We are told that Falluja had to be destroyed, in order to carry out

elections to an Iraqi constituent assembly on the 27th January 2005.

We will see whether any elections take place. There are

those among us who doubt whether such elections were actually intended in any more than a fictional exit

strategy for the purposes of another election, in the United States. Mr.

Bush has won that, and may not need the one in Iraq. It is

greatly to be doubted whether the conditions for an election exist in the aftermath of the destruction of

Falluja.

Kofi Annan warned Bush, Blair, and their puppet, Iyad Allawi, that

elections required “a broader spectrum of Iraqis to join the political process” and the persuasion of

“elements who are currently alienated from, or sceptical about, the transition process”.

He expressed his “increasing concern at the prospect of an escalation in violence, which I fear

could be very disruptive for Iraq’s political transition”.

Kofi Annan was entirely specific.

“I

have in mind not only the risk of increased insurgent violence, but also reports of major military offensives

being planned by the multinational force in key localities such as Falluja.

I wish to express to you my particular concern about the safety and protection of civilians.

Fighting is likely to take place mostly in densely populated urban areas, with an obvious risk of

civilian casualties … The threat or actual use of force not

only risks deepening the sense of alienation of certain communities, but would also reinforce perceptions

among the Iraqi population of a continued military occupation.”

Guernica was struck down out of a clear sky, and none of the victims

expected it. But Falluja was planned in great detail for months

before the culmination of the American election made it possible to risk the criticism of domestic public

opinion. Indeed the British allies were redeployed to seal off

what was eloquently described as the “rat run” from Falluja, in spite of the consternation in Scotland,

whose Black Watch soldiers were put at very dire risk. All that

took time. It took time, up to two months, to cut off the water

supplies to Tall Afar, Samarra, and Falluja. We publish in our

dossier a careful report by Cambridge Solidarity with Iraq, which describes how this was done, in breach of

international humanitarian law, and without consultation with any of the allies.

Towards the end of a week of remorseless bombing and bombardment, the Red Crescent succeeded in

sending a convoy of food and medicines into the outskirts of Falluja. American

forces denied them the right to move beyond a hospital on the outskirts of the town.

As happened before, during the invasion by coalition forces, news has

been comprehensively and carefully managed, so that we cannot tell what the true level of casualties has

been. At the end of the first week, the Americans were reported

as having sustained 38 deaths and to have suffered 275 other casualties.

They also claim to have killed, variously, 1000 or 1600 insurgents and to have captured between 450

and 550 others. But the insurgents claim vastly smaller

casualties. Al-Dulaimi said that the number of Falluja’s

defenders, “martyrs who were killed”, did not exceed 100. “We

lost 15 of our men”, he said. Nobody, but nobody, can offer

any credible figures about the civilian death toll. We shall not

be able to calculate anything approaching the true mortality for some time, just as it took more than a year

before The Lancet was able to publish research about the true human cost of the occupation.

What

is absolutely clear is that large swathes of Falluja have been literally pulverised, ground to powder by the

kind of destructive machine that Hermann Goering could hardly imagine. Just

as we do not know how many innocents have been massacred, neither do the Iraqi people.

But they know about the moral depth of this atrocity. They

know that Iraqi lives do not count for the coalition, nor for its servants in the Iraqi detachments of

American intelligence, who now call themselves Ministers.

The highest Shia authority in Baghdad, Shaikh Muhammad Mahdi al-Khalissi,

condemned the assault on Falluja as an “aggression and dirty war”, and said:

“No

matter how powerful the occupation forces are, they will be driven out of Iraq sooner or later.

The current savage military attack on Falluja by US occupation forces and the US appointed Iraqi

Government is an act of mass murder and a crime of war”.

The

Association of Muslim Scholars, a Sunni powerhouse, proclaimed a Fatwa prohibiting Iraqis from joining in the

American attack. Muqtada al-Sadr withdrew the support of his

movement for the January elections. His aide declared:

“There

has been a chance for a peaceful solution, but the Government always chooses the military solution because

the United States wants that”.

Meantime, open insurgency rages in Kirkuk, Tikrit, Samarra, Baiji, and in

Iraq’s third largest city, Mosul. Other towns have given

refuge to fighters fleeing from Falluja itself, as has Ar Ramadi.

The

official story put out by the coalition is that strong contingents of foreign fighters and supporters of the

old regime constitute tightly knit minorities who can be hunted down, to the relief of the majority of peace

loving Iraqis. The destruction of Falluja will destroy this

myth. The American occupation stands revealed, red in tooth and

claw. It does not intend to go away

It would like to establish economically viable bases, for sure, and to withdraw many soldiers for

deployment elsewhere. But it does not intend to relinquish

control of the resources it had thought it had won. Oil remains

very high on the agenda.

Quite why Tony Blair supports these brigands is very difficult to

understand. There may not be many spoils of war for him.

But he has earned a due share of the opprobrium which attaches to war criminals.

A brave attempt to impeach him has been made on the initiative of Plaid Cymru’s MP Adam Price, and

we have published the magisterial indictment prepared by Glen Rangwala and Dan Plesch. The impeachment

concerns the lies that were told in preparation for the invasion. More

lies are following all the time, and they are more desperately told, as the truth about this illegal war, and

this incredibly brutal occupation, begins to make itself plain. Unlike

President Bush, the Prime Minister’s election is in front of him. It

is difficult to see how anyone with a conscience will be able to support the renewal of his mandate.

Editorial:

The Spokesman no.84, Journal of the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation (www.russfound.org)

This Night In Fallujah: Lailat Al Qadr In Ramadan

© Copyright 2004 Sam Hamod

Tonight, in Fallujah

We wait

For the known

For the follow-up

To the fighter planes

To the rockets

To the long days of shelling

To the depleted uranium killing us slowly,

We wait

To see their tanks

Their tanks will come first

They remind us of the Israelis

They remind us American planes killed our cousins

In Palestine

Killed them with American rockets,

Now

They have come for us

We were living

Just living our lives,

With our wives and children,

Just like the Americans

They went to school, they did their lessons

They ran innocently

In the schoolyards

And on weekends the boys

Would tease the girls

In the marketplace, but

Dare not let the mother or

Father of the girl see, the girls

Would twist their

Hair, their smiles

And blush

Away from the eyes

Of their mothers

We were just living

Not looking to fight, just

Wanting to be

Left alone

But they came

Hunting us, like

Animals, like wild

Things, they came

Shooting, randomly,

Dropping 500 pound bombs

Destroying our mosques, our

Churches, our schools, our

Hospitals, our water, our

Electricity—they bombed

Us back 300 years

But, we

Just wanted to live

Just wanted to pray each day

In our mosques, raise our

Children, take care of our

Wives, our old fathers and

Mothers, we are not for

Fighting—but now

There is no

Choice—what good

Would it be to run

To be shot down

Like an animal on the run,

Now it is time, even with

The small weapons

We have, we shall stand now

To protect what we have

To claim our own homes, to claim

Our own peace

They are strange

These Christians, not like

My cousin’s wife

Who is Christian, in our

Christian churches, they say

Jesus said, “Blessed are the peacemakers,”

“God’s greatest gift is mercy,”

but these men come

with large crosses on their chests,

their ministers teach them songs about

killing and killing for Jesus, these

Americans are strange, we had

Always heard

They were peaceful people, people

Who wanted what we wanted,

Peace, life, justice,

Decency, education,

We had heard----

So now they come,

Loudspeakers on their jeeps, loudspeakers

And louder music, drums banging,

They tell us to surrender or die, they have

Iraqi slaves among them, some of whom

Will, at the last minute, turn on these

Americans, kill some

And themselves be killed,

We have on our side, Allah

We have on our side, our families,

Our homes, our thousands of years

Of having to defend ourselves

From Persians, from Greeks, from

Romans, from Mongols, from Crusaders,

From Turks, from British—now

This new evil, this new devil

Flying their flags, red, white and blue,

Blaring their music and harsh words,

We see their eyes now,

They are young, like

Us, they are afraid, yet

They want to kill us, we

Are “ragheads,” “we are animals,”

We are “assholes,” “we are terrorists”

And every other name you can think of

And they have come to kill us

To wipe our city off the maps of the world,

Off the map of Iraq, they say

They come at the order of the exile

The Americans sent to rule us, Iyad

Allawi, Iyad the whore, Iyad the munafik,

Iyad the devil—and yes,

We shall die, but Allah knows

Who is the evil one

And who is the one who fights in his name,

There is always that short term victory

For the devils

But their long run is not long

And they too shall die

We do not want to die, but

We understand dying is only

Part of living, death is always

Waiting, sometimes

Patiently, other times

Takes us swiftly, but we understand

This is the will of Allah

Some of us must die

So that others will

Understand

Just what is going on

So that others will see

So that others will resist even more

Our deaths will echo in Saudi Arabia,

In Kuwait, in the Muslim halls of the world, in

The cries of our women, in the history of our

Muslim people, in the Khutba’s on Friday’s

Prayers—they know

That we die during Ramadan, they know

We die gloriously at the hand of the heathens, at

The hands of the unbelievers, for the sake of

What the Qur’an taught us,

To protect our families, our homes, our country and

Most of all to protect our mosques

And Islam

So we have stayed to fight

And die during Ramadan, this

Most holy of months, this Ramadan

That requires so much

Discipline and faith, this Ramadan

That is the month of our sign of commitment

To Allah, it is a glorious month

In which to fight, and if necessary

To die

No, we are not mad

We do not wish to die

We have more desire to live

Than these devils who have invaded our land

Attacked our fathers and mothers, who

Have raped our women, who have

Tortured our cousins and brothers in their

Prisons, all in the name of

“democracy,” and “liberty,” and “freedom”—

how hollow their words

how hollow their lies

how hollow their attacks on us

they do not realize

we do not die, we

live, we live

on now, as martyrs, as

heroes, as men who

were not afraid to die, as men

who believed in the Deen, in Allah,

in the same God they proclaim but do not truly follow—

but his wrath is coming

his wrath shall be coming upon them—

if they survive our fight, they

are being poisoned, just as we have been poisoned,

the depleted uranium has poisoned their blood,

has poisoned the eggs in their sperm,

has poisoned their lives

so when they have deformed children, the

children will be witnesses to their killing

us, to their killing of their own souls,

to their killing their own families, and

what of those who will go mad, whose

nightmares will not let them ever sleep

another peaceful night

and what will their faces tell them

when they look in the mirror

when they look on their dressers

and see the pieces of metal

they were given for killing us

in our own homes, in own cities, in

our own mosques and churches,

what will their eyes say,

what will they say when their twisted

lies are uncovered, when the rest of the

world speaks of their massacres of

women and children, of old men, of

bombing hospitals, what will they

do when they see the smirking face

of their presidents, their senators, their

leaders who have allowed them to do this,

have ordered them to do this

—and

what will they say to Jesus

when he speaks to them on Judgement Day

when he asks why they killed—

why they did not say, NO

why they did not prefer prison over killing of innocent

civilians, and to the pilots who

fly freely, without concern of any reprisal, F16s rocketing

our city day after day, night after night, surely

they will not fly with the angels, but

shall burn even worse than the rest—

and so we hear the rockets and hear the bombs

during our maghrib prayer, we have heard since our fajr

prayers, we do not much feel like iftar, the food

has lost some of its taste, no one wants to die,

no one wants to leave their wife and children,

no one wants never to see their father or mother again,

no one wants to have to fight, just to live,

no one wants to have to kill another human being—at least

none of us,

we were living peacefully in our city,

we did not attack anyone, we

did not do anything worse than defend ourselves,

and for that

now we know we must die, we

know that unless Allah produces a miracle

or sends legions of angels to protect us

that the planes will attack

with the tanks that will crush us

with the rockets and snipers who

will split our bodies into pieces, whose

concussions will split our heads open,

whose noise will puncture our eardrums

until we bleed

and like our blessed Prophet Jesus, who came

before our blessed Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him,

we shall die, just as Jesus

was martyred—we shall be martyred

by the new Roman, the new crusader army,

on this Night of Power, where Allah’s message of

righteousness and courage is clear, where

we renew our commitment to our God,

where we know he gives us everlasting life

though we may die tonight on the earth,

we shall live forever, in Allah’s hands,

We shall live

in history, and the world, yea

the world will remember

we stood and fought this day,

knowing we would die

but knowing that death is only a moment

in God’s time, in Allah’s time

and that those who kill us today

may live long and tortured lives

when they realize what evil they have done

and those evil men

who ordered them on, Allawi, Bush,

Cheney, Wolfowitz, Abizaid, Myers and the rest,

Allah will take care of them

On the earth and on Judgement Day,

And the men who did not have the courage to

Say, No,

They will suffer each hour, each day

For the rest of their earthly days,

For it is written, that whosoever kills a believer

During Ramadan, will suffer hellfire and damnation

For eternity

So we choose to stand, to die if we must,

But during this blessed month of Ramadan

There is no death to the believer

Only the knowledge that Allah’s ways

Are beyond our understanding—we may not

Be on the earth to see what will happen

but we will be looking

Down from Heaven

And we shall see Allah visit his wrath

On those who come to kill us in our homes,

In our city, in our country, in our churches, in

Our mosques—and though we may die,

Like these days of our battle,

Our spirits

Will live forever

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Lailat Al Qadr: The Night of Power where God’s message is clear to the world, where God/Allah blesses the

righteous and condemns the evil ones.

Ramadan: The Muslim Holy Month of fasting, prayer and renewed commitment to God/Allah (Allah is the Arabic

word for God, used by Muslims and Christians alike in the Middle East).

Qhutba: The Muslim sermon on prayer days in the mosques.

Fallujah: The homecoming and the homeless

By Patrick Cockburn in Baghdad and Kim Sengupta

http://news.independent.co.uk/world/middle_east/story.jsp?story=591998

11 December 2004

The Black Watch arrives back in Britain this morning home in time for Christmas as Tony Blair had

promised.

The regiment's five-week mission the toughest British troops have faced since the invasion of Iraq 21

months ago made possible the US assault on Fallujah, which now lies in ruins. Five Black Watch soldiers

died, and no one doubts the dedication they brought to the task, particularly as the regiment knew it was

facing the axe in a forthcoming review of the Army.

As they left Camp Dogwood for the last time yesterday, one officer spoke of the frustration among the

850-strong contingent when it was ordered north to support the American forces. He said: "The whole

deployment was, of course, heavily politicised from the beginning. Some soldiers criticised Tony Blair by

name. There was a feeling that we were being used, and that made it difficult to focus initially on our

mission."

They are delighted to be back home, and will no doubt enjoy emotional reunions with their families. But

what of the mission they left behind, and the city that was its target? Yesterday, the first independent

reports began to emerge from a flattened city which is facing an unprecedented, permanent security

crackdown, and an uncertain future.

The assault by 10,000 US troops began on 8 November, just after the US presidential elections: its aim,

to clear a city regarded by the Americans as a hotbed of insurgency.

More than 70 marines died, and 1,600 rebels. But no one knows the civilian casualty toll this in a city

which once numbered 300,000. Indeed, there are no estimates of how many people are still there, or how many

escaped to neighbouring towns and to Baghdad before the assault got under way.

Ahmed Rawi, a Red Cross spokesman, said yesterday: "No one knows how many families are inside the city."

The Red Cross team which entered without escort and left before curfew met no residents, apart from

engineers and technicians. The Red Cross reported that hundreds of dead bodies remain stacked inside a

potato chip warehouse on the outskirts. Some of the bodies were too badly decomposed to be identified. Raw

sewage runs through the streets.

All this, and there are no humanitarian workers working inside the city. When the first of Fallujah's

refugees are allowed to return on Christmas Eve, they will be funnelled through five checkpoints. Each will

have their fingerprints taken, along with DNA samples and retina scans. Residents will be issued with badges

with their home addresses on them, and it will be an offence not to wear it at all times. No civilian

vehicles will be allowed in the city in an effort to thwart suicide bombers. One idea floated by the US is

for all males in Fallujah be compelled to join work battalions in which they will be paid to clear rubble

and rebuild houses.

American officers say the hardline approach is legal under martial law regulations issued last month by

the interim government of Iyad Allawi. But they appear a little embarrassed by the Orwellian overtones of

their plan. Major Francis Piccoli, a spokesman for the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force, admitted: "Some may

see this as a 'Big Brother is watching over you' experiment. But, in reality, it's a simple security measure

to keep the insurgents from coming back."

Before the battle of Fallujah, the US repeatedly said that foreign fighters and Islamic zealots were

orchestrating guerrilla attacks on US soldiers from the city. But the planned measures presume everybody in

Fallujah to be a potential supporter of the resistance.

Fallujah will be the first community in Iraq to be subjected to such tough identification tests. So far,

they have been used mainly against detainees there are 2,000 people still held on suspicion of aiding the

insurgents.

The city's capture was supposed to break the back of the insurgency and open the way for people to take

part in the Iraqi elections on 30 January. Yet, so far, there is little sign that resistance to the US and

the interim government is weakening in Sunni Muslim districts in central and northern Iraq.

The plan to identify and monitor all civilians is very similar to a plan implemented by Saddam Hussein to

separate insurgents from civilians in Iraqi Kurdistan during the 1980s.

Against all this background, the officer from the Black Watch said as he prepared to leave: "Was it worth

it? Of course, we have all got our private thoughts about this war. There was a lot of unease about being

identified too much with the Americans and Fallujah ... you have to hope at the end that we did some good.

Only time will tell."

Fallujah: the April 2004 Siege

by Jo Wilding (April 14 2004)

I’m sorry it’s so long, but please, please read and forward widely.

The truth of what’s happening in Falluja has to get out.

Hamoudie, my thoughts are with you.

April 11th Falluja

Trucks, oil tankers, tanks are burning on the highway east to Falluja. A stream of boys and men

goes to and from a lorry that’s not burnt, stripping it bare. We turn onto the back roads through Abu

Ghraib, Nuha and Ahrar singing in Arabic, past the vehicles full of people and a few possessions,

heading the other way, past the improvised refreshment posts along the way where boys throw food

through the windows into the bus for us and for the people inside still inside Falluja.

The bus is following a car with the nephew of a local sheikh and a guide who has contacts with the

Mujahedin and has cleared this with them. The reason I’m on the bus is that a journalist I knew turned

up at my door at about 11 at night telling me things were desperate in Falluja, he’d been bringing out

children with their limbs blown off, the US soldiers were going around telling people to leave by dusk

or be killed, but then when people fled with whatever they could carry, they were being stopped at the

US military checkpoint on the edge of town and not let out, trapped, watching the sun go down.

He said aid vehicles and the media were being turned away. He said there was some medical aid that

needed to go in and there was a better chance of it getting there with foreigners, westerners, to get

through the american checkpoints. The rest of the way was secured with the armed groups who control

the roads we’d travel on. We’d take in the medical supplies, see what else we could do to help and

then use the bus to bring out people who needed to leave.

I’ll spare you the whole decision making process, all the questions we all asked ourselves and each

other, and you can spare me the accusations of madness, but what it came down to was this: if I don’t

do it, who will? Either way, we arrive in one piece.

We pile the stuff in the corridor and the boxes are torn open straightaway, the blankets most

welcomed. It’s not a hospital at all but a clinic, a private doctor’s surgery treating people free

since air strikes destroyed the town’s main hospital. Another has been improvised in a car garage.

There’s no anaesthetic. The blood bags are in a drinks fridge and the doctors warm them up under the

hot tap in an unhygienic toilet.

Screaming women come in, praying, slapping their chests and faces. Ummi, my mother, one cries. I hold

her until Maki, a consultant and acting director of the clinic, brings me to the bed where a child of

about ten is lying with a bullet wound to the head. A smaller child is being treated for a similar

injury in the next bed. A US sniper hit them and their grandmother as they left their home to flee

Falluja.

The lights go out, the fan stops and in the sudden quiet someone holds up the flame of a cigarette

lighter for the doctor to carry on operating by. The electricity to the town has been cut off for days

and when the generator runs out of petrol they just have to manage till it comes back on. Dave quickly

donates his torch. The children are not going to live.

“Come,” says Maki and ushers me alone into a room where an old woman has just had an abdominal

bullet wound stitched up. Another in her leg is being dressed, the bed under her foot soaked with

blood, a white flag still clutched in her hand and the same story: I was leaving my home to go to

Baghdad when I was hit by a US sniper. Some of the town is held by US marines, other parts by the

local fighters. Their homes are in the US controlled area and they are adamant that the snipers were

US marines.

Snipers are causing not just carnage but also the paralysis of the ambulance and evacuation

services. The biggest hospital after the main one was bombed is in US territory and cut off from the

clinic by snipers. The ambulance has been repaired four times after bullet damage. Bodies are lying in

the streets because no one can go to collect them without being shot.

Some said we were mad to come to Iraq; quite a few said we were completely insane to come to

Falluja and now there are people telling me that getting in the back of the pick up to go past the

snipers and get sick and injured people is the craziest thing they’ve ever seen. I know, though, that

if we don’t, no one will.

He’s holding a white flag with a red crescent on; I don’t know his name. The men we pass wave us on

when the driver explains where we’re going. The silence is ferocious in the no man’s land between the

pick up at the edge of the Mujahedin territory, which has just gone from our sight around the last

corner and the marines’ line beyond the next wall; no birds, no music, no indication that anyone is

still living until a gate opens opposite and a woman comes out, points.

We edge along to the hole in the wall where we can see the car, spent mortar shells around it. The

feet are visible, crossed, in the gutter. I think he’s dead already. The snipers are visible too, two

of them on the corner of the building. As yet I think they can’t see us so we need to let them know

we’re there.

“Hello,” I bellow at the top of my voice. “Can you hear me?” They must. They’re about 30 metres

from us, maybe less, and it’s so still you could hear the flies buzzing at fifty paces. I repeat

myself a few times, still without reply, so decide to explain myself a bit more.

“We are a medical team. We want to remove this wounded man. Is it OK for us to come out and get

him? Can you give us a signal that it’s OK?”

I’m sure they can hear me but they’re still not responding. Maybe they didn’t understand it all, so

I say the same again. Dave yells too in his US accent. I yell again. Finally I think I hear a shout

back. Not sure, I call again.

“Hello.”

“Yeah.”

“Can we come out and get him?”

“Yeah,”

Slowly, our hands up, we go out. The black cloud that rises to greet us carries with it a hot, sour

smell. Solidified, his legs are heavy. I leave them to Rana and Dave, our guide lifting under his

hips. The Kalashnikov is attached by sticky blood to is hair and hand and we don’t want it with us so

I put my foot on it as I pick up his shoulders and his blood falls out through the hole in his back.

We heave him into the pick up as best we can and try to outrun the flies.

I suppose he was wearing flip flops because he’s barefoot now, no more than 20 years old, in

imitation Nike pants and a blue and black striped football shirt with a big 28 on the back. As the

orderlies form the clinic pull the young fighter off the pick up, yellow fluid pours from his mouth

and they flip him over, face up, the way into the clinic clearing in front of them, straight up the

ramp into the makeshift morgue.

We wash the blood off our hands and get in the ambulance. There are people trapped in the other

hospital who need to go to Baghdad. Siren screaming, lights flashing, we huddle on the floor of the

ambulance, passports and ID cards held out the windows. We pack it with people, one with his chest

taped together and a drip, one on a stretcher, legs jerking violently so I have to hold them down as

we wheel him out, lifting him over steps.

The hospital is better able to treat them than the clinic but hasn’t got enough of anything to sort

them out properly and the only way to get them to Baghdad on our bus, which means they have to go to

the clinic. We’re crammed on the floor of the ambulance in case it’s shot at. Nisareen, a woman doctor

about my age, can’t stop a few tears once we’re out.

The doctor rushes out to meet me: “Can you go to fetch a lady, she is pregnant and she is

delivering the baby too soon?”

Azzam is driving, Ahmed in the middle directing him and me by the window, the visible foreigner,

the passport. Something scatters across my hand, simultaneous with the crashing of a bullet through

the ambulance, some plastic part dislodged, flying through the window.

We stop, turn off the siren, keep the blue light flashing, wait, eyes on the silhouettes of men in

US marine uniforms on the corners of the buildings. Several shots come. We duck, get as low as

possible and I can see tiny red lights whipping past the window, past my head. Some, it’s hard to

tell, are hitting the ambulance I start singing. What else do you do when someone’s shooting at you? A

tyre bursts with an enormous noise and a jerk of the vehicle.

I’m outraged. We’re trying to get to a woman who’s giving birth without any medical attention,

without electricity, in a city under siege, in a clearly marked ambulance, and you’re shooting at us.

How dare you?

How dare you?

Azzam grabs the gear stick and gets the ambulance into reverse, another tyre bursting as we go over

the ridge in the centre of the road , the sots still coming as we flee around the corner. I carry on

singing. The wheels are scraping, burst rubber burning on the road.

The men run for a stretcher as we arrive and I shake my head. They spot the new bullet holes and

run to see if we’re OK. Is there any other way to get to her, I want to know. La, maaku tarieq. There

is no other way. They say we did the right thing. They say they’ve fixed the ambulance four times

already and they’ll fix it again but the radiator’s gone and the wheels are buckled and se’s still at

home in the dark giving birth alone. I let her down.

We can’t go out again. For one thing there’s no ambulance and besides it’s dark now and that means

our foreign faces can’t protect the people who go out with us or the people we pick up. Maki is the

acting director of the place. He says he hated Saddam but now he hates the Americans more.

We take off the blue gowns as the sky starts exploding somewhere beyond the building opposite.

Minutes later a car roars up to the clinic. I can hear him screaming before I can see that there’s no

skin left on his body. He’s burnt from head to foot. For sure there’s nothing they can do. He’ll die

of dehydration within a few days.

Another man is pulled from the car onto a stretcher. Cluster bombs, they say, although it’s not

clear whether they mean one or both of them. We set off walking to Mr Yasser’s house, waiting at each

corner for someone to check the street before we cross. A ball of fire falls from a plane, splits into

smaller balls of bright white lights. I think they’re cluster bombs, because cluster bombs are in the

front of my mind, but they vanish, just magnesium flares, incredibly bright but short-lived, giving a

flash picture of the town from above.

Yasser asks us all to introduce ourselves. I tell him I’m training to be a lawyer. One of the other

men asks whether I know about international law. They want to know about the law on war crimes, what a

war crime is. I tell them I know some of the Geneva Conventions, that I’ll bring some information next

time I come and we can get someone to explain it in Arabic.

We bring up the matter of Nayoko. This group of fighters has nothing to do with the ones who are

holding the Japanese hostages, but while they’re thanking us for what we did this evening, we talk

about the things Nayoko did for the street kids, how much they loved her. They can’t promise anything

but that they’ll try and find out where she is and try to persuade the group to let her and the others

go. I don’t suppose it will make any difference. They’re busy fighting a war in Falluja. They’re

unconnected with the other group. But it can’t hurt to try.

The planes are above us all night so that as I doze I forget I’m not on a long distance flight, the

constant bass note of an unmanned reconnaissance drone overlaid with the frantic thrash of jets and

the dull beat of helicopters and interrupted by the explosions.

In the morning I make balloon dogs, giraffes and elephants for the little one, Abdullah, Aboudi,

who’s clearly distressed by the noise of the aircraft and explosions. I blow bubbles which he follows

with his eyes. Finally, finally, I score a smile. The twins, thirteen years old, laugh too, one of

them an ambulance driver, both said to be handy with a Kalashnikov.

The doctors look haggard in the morning. None has slept more than a couple of hours a night for a

week. One as had only eight hours of sleep in the last seven days, missing the funerals of his brother

and aunt because he was needed at the hospital.

“The dead we cannot help,” Jassim said. “I must worry about the injured.”

We go again, Dave, Rana and me, this time in a pick up. There are some sick people close to the

marines’ line who need evacuating. No one dares come out of their house because the marines are on top

of the buildings shooting at anything that moves. Saad fetches us a white flag and tells us not to

worry, he’s checked and secured the road, no Mujahedin will fire at us, that peace is upon us, this

eleven year old child, his face covered with a keffiyeh, but for is bright brown eyes, his AK47 almost

as tall as he is.

We shout again to the soldiers, hold up the flag with a red crescent sprayed onto it. Two come down

from the building, cover this side and Rana mutters, “Allahu akbar. Please nobody take a shot at

them.”

We jump down and tell them we need to get some sick people from the houses and they want Rana to go

and bring out the family from the house whose roof they’re on. Thirteen women and children are still

inside, in one room, without food and water for the last 24 hours.

“We’re going to be going through soon clearing the houses,” the senior one says.

“What does that mean, clearing the houses?”

“Going into every one searching for weapons.” He’s checking his watch, can’t tell me what will

start when, of course, but there’s going to be air strikes in support. “If you’re going to do tis you

gotta do it soon.”

First we go down the street we were sent to. There’s a man, face down, in a white dishdasha, a

small round red stain on his back. We run to him. Again the flies ave got there first. Dave is at his

shoulders, I’m by his knees and as we reach to roll him onto the stretcher Dave’s hand goes through

his chest, through the cavity left by the bullet that entered so neatly through his back and blew his

heart out.

There’s no weapon in his hand. Only when we arrive, his sons come out, crying, shouting. He was

unarmed, they scream. He was unarmed. He just went out the gate and they shot him. None of them have

dared come out since. No one had dared come to get his body, horrified, terrified, forced to violate

the traditions of treating the body immediately. They couldn’t have known we were coming so it’s

inconceivable that anyone came out and retrieved a weapon but left the body.

He was unarmed, 55 years old, shot in the back.

We cover his face, carry him to the pick up. There’s nothing to cover his body with. The sick woman

is helped out of the house, the little girls around her hugging cloth bags to their bodies,

whispering, “Baba. Baba.” Daddy. Shaking, they let us go first, hands up, around the corner, then we

usher them to the cab of the pick up, shielding their heads so they can’t see him, the cuddly fat man

stiff in the back.

The people seem to pour out of the houses now in the hope we can escort them safely out of the line

of fire, kids, women, men, anxiously asking us whether they can all go, or only the women and

children. We go to ask. The young marine tells us that men of fighting age can’t leave. What’s

fighting age, I want to know. He contemplates. Anything under forty five. No lower limit.

It appals me that all those men would be trapped in a city which is about to be destroyed. Not all

of them are fighters, not all are armed. It’s going to happen out of the view of the world, out of

sight of the media, because most of the media in Falluja is embedded with the marines or turned away

at the outskirts. Before we can pass the message on, two explosions scatter the crowd in the side

street back into their houses.

Rana’s with the marines evacuating the family from the house they’re occupying. The pick up isn’t

back yet. The families are hiding behind their walls. We wait, because there’s nothing else we can do.

We wait in no man’s land. The marines, at least, are watching us through binoculars; maybe the local

fighters are too.

I’ve got a disappearing hanky in my pocket so while I’m sitting like a lemon, nowhere to go,

gunfire and explosions aplenty all around, I make the hanky disappear, reappear, disappear. It’s

always best, I think, to seem completely unthreatening and completely unconcerned, so no one worries

about you enough to shoot. We can’t wait too long though. Rana’s been gone ages. We have to go and get

her to hurry. There’s a young man in the group. She’s talked them into letting him leave too.

A man wants to use his police car to carry some of the people, a couple of elderly ones who can’t

walk far, the smallest children. It’s missing a door. Who knows if he was really a police car or the

car was reappropriated and just ended up there? It didn’t matter if it got more people out faster.

They creep from their houses, huddle by the wall, follow us out, their hands up too, and walk up the

street clutching babies, bags, each other.

The pick up gets back and we shovel as many onto it as we can as an ambulance arrives from

somewhere. A young man waves from the doorway of what’s left of a house, his upper body bare, a blood

soaked bandage around his arm, probably a fighter but it makes no difference once someone is wounded

and unarmed. Getting the dead isn’t essential. Like the doctor said, the dead don’t need help, but if

it’s easy enough then we will. Since we’re already OK with the soldiers and the ambulance is here, we

run down to fetch them in. It’s important in Islam to bury the body straightaway.

The ambulance follows us down. The soldiers start shouting in English at us for it to stop,

pointing guns. It’s moving fast. We’re all yelling, signalling for it to stop but it seems to take

forever for the driver to hear and see us. It stops. It stops, before they open fire. We haul them

onto the stretchers and run, shove them in the back. Rana squeezes in the front with the wounded man

and Dave and I crouch in the back beside the bodies. He says he had allergies as a kid and hasn’t got

much sense of smell. I wish, retrospectively, for childhood allergies, and stick my head out the

window.

The bus is going to leave, taking the injured people back to Baghdad, the man with the burns, one

of the women who was shot in the jaw and shoulder by a sniper, several others. Rana says she’s staying

to help. Dave and I don’t hesitate: we’re staying too. “If I don’t do it, who will?” has become an

accidental motto and I’m acutely aware after the last foray how many people, how many women and

children, are still in their houses either because they’ve got nowhere to go, because they’re scared

to go out of the door or because they’ve chosen to stay.

To begin with it’s agreed, then Azzam says we have to go. He hasn’t got contacts with every armed

group, only with some. There are different issues to square with each one. We need to get these people

back to Baghdad as quickly as we can. If we’re kidnapped or killed it will cause even more problems,

so it’s better that we just get on the bus and leave and come back with him as soon as possible.

It hurts to climb onto the bus when the doctor has just asked us to go and evacuate some more

people. I hate the fact that a qualified medic can’t travel in the ambulance but I can, just because I

look like the sniper’s sister or one of his mates, but that’s the way it is today and the way it was

yesterday and I feel like a traitor for leaving, but I can’t see where I’ve got a choice. It’s a war

now and as alien as it is to me to do what I’m told, for once I’ve got to.

Jassim is scared. He harangues Mohammed constantly, tries to pull him out of the driver’s seat wile

we’re moving. The woman with the gunshot wound is on the back seat, the man with the burns in front of

her, being fanned with cardboard from the empty boxes, his intravenous drips swinging from the rail

along the ceiling of the bus. It’s hot. It must be unbearable for him.

Saad comes onto the bus to wish us well for the journey. He shakes Dave’s hand and then mine. I

hold his in both of mine and tell him “Dir balak,” take care, as if I could say anything more stupid

to a pre-teen Mujahedin with an AK47 in his other hand, and our eyes meet and stay fixed, his full of

fire and fear.

Can’t I take him away? Can’t I take him somewhere he can be a child? Can’t I make him a balloon

giraffe and give him some drawing pens and tell him not to forget to brush his teeth? Can’t I find the

person who put the rifle in the hands of that little boy? Can’t I tell someone about what that does to

a child? Do I have to leave him here where there are heavily armed men all around him and lots of them

are not on his side, however many sides there are in all of this? And of course I do. I do have to

leave him, like child soldiers everywhere.

The way back is tense, the bus almost getting stuck in a dip in the sand, people escaping in

anything, even piled on the trailer of a tractor, lines of cars and pick ups and buses ferrying people

to the dubious sanctuary of Baghdad, lines of men in vehicles queuing to get back into the city having

got their families to safety, either to fight or to help evacuate more people. The driver, Jassim, the

father, ignores Azzam and takes a different road so that suddenly we’re not following the lead car and

we’re on a road that’s controlled by a different armed group than the ones which know us.

A crowd of men waves guns to stop the bus. Somehow they apparently believe that there are American

soldiers on the bus, as if they wouldn’t be in tanks or helicopters, and there are men getting out of

their cars with shouts of “Sahafa Amreeki,” American journalists. The passengers shout out of the

windows, “Ana min Falluja,” I am from Falluja. Gunmen run onto the bus and see that it’s true, there

are sick and injured and old people, Iraqis, and then relax, wave us on.

We stop in Abu Ghraib and swap seats, foreigners in the front, Iraqis less visible, headscarves off

so we look more western. The American soldiers are so happy to see westerners they don’t mind too much

about the Iraqis with us, search the men and the bus, leave the women unsearched because there are no

women soldiers to search us. Mohammed keeps asking me if things are going to be OK.

“Al-melaach wiyana, ” I tell him. The angels are with us. He laughs.

And then we’re in Baghdad, delivering them to the hospitals, Nuha in tears as they take the burnt

man off groaning and whimpering. She puts her arms around me and asks me to be her friend. I make her

feel less isolated, she says, less alone.

And the satellite news says the cease-fire is holding and George Bush says to the troops on Easter

Sunday that, “I know what we’re doing in Iraq is right.” Shooting unarmed men in the back outside

their family home is right. Shooting grandmothers with white flags is right? Shooting at women and

children who are fleeing their homes is right? Firing at ambulances is right?

Well George, I know too now. I know what it looks like when you brutalise people so much that

they’ve nothing left to lose. I know what it looks like when an operation is being done without

anaesthetic because the hospitals are destroyed or under sniper fire and the city’s under siege and

aid isn’t getting in properly. I know what it sounds like too. I know what it looks like when tracer

bullets are passing your head, even though you’re in an ambulance. I know what it looks like when a

man’s chest is no longer inside him and what it smells like and I know what it looks like when his

wife and children pour out of his house.

It’s a crime and it’s a disgrace to us all.

Dahr Jamail's reports of the

april 2004 Siege

April 03, 2004

From Amman, on Falluja

Amman, Jordan - By now I imagine everyone has been properly inundated with the images of the

scorched bodies of the 'American Civilians' (as properly parroted by the corporate media) in

Falluja. In case I missed it before departing, I had one last chance to catch it on the countless

televisions in JFK airport, then on the front page of the NY Times on the plane.

I thought it was interesting, because what accompanied this story was a strange little

phenomenon I've seen many times in Iraq. The first bit of news released on the attack referred to

the men killed as 'contractors', and even showed an Iraqi man handling the dog tags of one of

them, and another man was holding a Department of Defense badge from another of the U.S. fighters

the Iraqis had killed. The same report mentioned that a collection of weapons was in one of the

vehicles as well.

Of course that was the last of that footage I saw. From then on, it was 'Americans killed by

Iraqis!', or 'Contractors Killed', over and over ad nauseum.

Well, it turns out these 'Americans killed by Iraqis' just happened to be four mercenaries

working for a N.C. Security Firm called Blackwater Security Consulting.

This subcontractor, along with countless others, is working to provide 'security' in Iraq.

Check out their website: because they even provide training for SWAT teams and former special

operations personnel.

I've been in Falluja when the entire city has been under collective punishment, which occurs

nearly everytime someone attacks a U.S. patrol there. People are enraged, and rightly so. So when

one of those white, shiny SUV's with the big black antenna drives by with guys with crew cuts in

them wearing body armor holding guns (yes, it is THAT obvious and easy to see), what do you think

might happen to them?

The other reason I bring this up is because of this: Last night I'm going through customs at

the airport in Amman, and I find myself standing in line behind five men with crewcuts and their

'handler', a little bit older fellow from Turkey (I saw his passport). The men were all in their

late 20's, to late 30's I'd say, and from their discussion had all been in Iraq before.

They wouldn't tell me who they were working for, but when they were lugging huge plastic boxes

with locks on them off the baggage belt, then went and hopped into their nice, white SUV, it was

pretty much a no-brainer.

Blackwater Security Consulting won a $35.7 million contract to train over 10,000 soldiers from

several states in the U.S. in the art of 'force protection,' according to Mother Jones magazine.

They also hire mercenaries from South Africa and other countries as well, and the pay in Iraq is

$1,000 per day. Wonder how that makes our soldiers feel, who make barely over that each month?

So the residents of Falluja are about to be 'pacified' because some of the resistance fighters

there killed what were most likely mercenaries who regularly attack and detain residents of

Falluja. The fog of war grows thicker in Iraq, as the privatization contracts continue to be

signed.

April 11, 2004

Slaughtering Civilians in Falluja

The scene in Falluja was so horrendous, that if I hadn’t seen it myself it would have been

difficult to comprehend. It still is-I’m having to force myself to write about it while the details

are still fresh in my mind.

We knew there was very little media coverage in Falluja, and the entire city had been sealed and

suffering from collective punishment via no water nor electricity for several days now. With only two

journalists there that I’d read reports from, I felt pulled to go and witness the atrocities which

were sure to be occurring.

With the help of some friends, we joined a small group of internationals to ride a large bus there

carrying a good load of humanitarian supplies, and with the hopes of bringing some of the wounded out

prior to the next American onslaught, which was due to kick off at any time now.

Even leaving Baghdad now is dangerous. The military continues to have Falluja sealed off, and this

includes shutting down the main highway between here and Jordan. The highway, even while still

leaving Baghdad, is desolate and littered with destroyed fuel tanker trucks-their smoldering carcuses

littering the highway. We rolled past a large M-1 Tank that was still burning under an overpass-which

had just been hit by the resistance.

At the first U.S. checkpoint the soldiers said they’d been there for 30 hours straight. After

being searched, we continued along bumpy dirt roads, winding our way through parts of Abu Ghraib,

steadily but slowly making our way towards besieged Falluja. While passing one of the small homes in

Abu Ghraib a small child yelled at the bus, “We will be mujahedeen until we die!”

We slowly worked our way back onto the highway, which was littered with smoking fuel tankers,

destroyed military tanks and Amored Personnel Carriers, and a lorry that had been hit that was

currently being looted by a nearby village, people running to and from the highway carrying away

boxes. It was a scene of pure devastation, and barely any other cars on the road.

We were absolutely the only bus on the highway, which of course made us more of a target. There

was a report of an Iraqi man who’d gone to the huge prison of Abu Ghraib to visit his brother, and

said there were clashes both in and outside the prison.

Once we turned off the highway, which the U.S. was perilously holding onto, there was no U.S.

military visible at all as we were in mujahedeen territory. Our bus wound its way through farm roads,

and each time we passed someone they would yell, “God bless you for going to Falluja!” Everyone we

passed was giving us the peace sign, waving, and giving the thumbs up.

As we neared Falluja, there were groups of children on the sides of the road handing out water and

bread to people coming into Falluja. They began literally throwing stacks of flat bread into the bus.

The fellowship and community spirit was unbelievable. Everyone yelling for us, cheering us on, groups

speckled along the road.

As we neared Falluja a huge mushroom caused by a large U.S. bomb rose from the city. So much for

the cease fire.

The closer we got to the city the more mujahedeen checkpoints we passed-at one, men with kefir

around their faces holding Kalashnikovs began shooting their guns in the air, showing their eagerness

to fight.

The city itself was virtually empty, aside from groups of mujahedeen standing on every other

street corner. It was a city at war. We rolled towards the one small clinic where we were to deliver

our medical supplies from INTERSOS, an Italian NGO. The small clinic is managed by Mr. Maki Al-Nazzal,

who was hired just 4 days ago to do so. He is not a doctor.

He hadn’t slept much, along with all of the doctors at the small clinic. It started with just

three doctors, but since the American’s bombed one of the hospitals, and were currently sniping

people as they attempted to enter/exit the main hospital, effectively there were only 2 small clinics

treating all of Falluja.

As I was there, an endless stream of women and children who’d been sniped by the Americans were

being raced into the dirty clinic, their cars speeding over the curb out front as their wailing

family members carried them in.

One woman and small child had been shot through the neck-the woman was making breathy gurgling

noises as the doctors frantically worked on her amongst her muffled moaning.

The small child, his eyes glazed and staring into space, continually vomited as the doctors raced

to save his small life.

After 30 minutes, it appeared as though neither of them would survive.

One victim of American aggression after another was brought into the clinic, nearly all of them

women and children.

This scene continued, off and on, into the night as the sniping continued. As evening approached

the nearby mosque loudspeaker announced that the mujehadeen had completely destroyed a U.S. convoy.

Gunfire filled the streets, along with jubilant yelling. As the mosque began blaring prayers, the

determination and confidence of the area was palpable.

One small boy of 11, his face covered by a kefir and toting around a Kalashnikov that was nearly

as big as he was, patrolled areas around the clinic-making sure they were secure. He was confident

and very eager for battle.

After we delivered the aid, three of my friends agreed to ride out on the one functioning

ambulance for the clinic to retrieve the wounded. Although the ambulance already had three bullet

holes from a U.S. sniper through the front windshield on the drivers side, the fact that two of them

are westerners was the only hope that soldiers would allow them to retrieve more wounded Iraqis. The

previous driver was wounded when one of the snipers shots grazed his head.

Bombs were heard sporadically exploding around the city, along with sporadic gunfire.

It grew dark, so we ended up spending the night with one of the local men who had filmed the

atrocities. He showed us footage of a dead baby who he claimed was torn from his mothers chest by

marines. Other footage of slain Iraqis.

The entire time in Falluja there was the constant buzzing of military drones. As we walked through

the empty streets towards the house we would sleep, a plane flew over us and dropped several flares.

We ran for a nearby wall to hunker down, afraid it was dropping cluster bombs. There had been reports

of this, as two of the last victims that arrived at the clinic were reported by the locals to have

been hit by cluster bombs-they were horribly burned and their bodies were shredded.

It was a long night-between being sick from drinking unfiltered water and the nagging concern of

the full invasion beginning, I didn’t sleep. Each time I would begin to slip into sleep, a jet would

fly over and I wondered if the full scale bombing would commence. Meanwhile, the drones continued to

buzz throughout Falluja.

The next morning we walked back to the clinic, and the mujahedeen in the area were extremely edgy,

expecting the invasion anytime. They were taking up positions to fight. One of my friends who’d done

another ambulance run to collect two bodies said that a marine she encountered had told them to

leave, because the military was about to use air support to begin ‘clearing the city.’ One of the

bodies they brought to the clinic was that of an old man who was shot by a sniper outside of his

home, while his wife and children sat wailing inside.

The family couldn’t reach his body, for fear of being sniped by the Americans themselves. His

stiff body was carried into the clinic with flies swarming above it.

The already insane situation continued to degrade, and by the time the wounded from the clinic

were loaded onto our bus and we prepared to leave, everyone felt the invasion was looming near.

American bombs continued to fall not far from us, and sporadic gunfire continued.

We drove out, past loads of mujahedeen at their posts along the streets. In a long line of

vehicles loaded with families, we slowly crept out of the embattled city, passing several military

vehicles on the outskirts of the city. When we took a wrong turn at one point and tried to go down a

road controlled by a different group of mujeheen, we were promptly surrounded by men cocking their

weapons and aiming them at us. The doctors and patients on board explained to them we were from

Falluja and on a humanitarian aid mission, so they let us go.

The trip back to Baghdad was slow, but relatively uneventful. We passed several more smoking

carcuses of vehicles destroyed by the freedom fighters-more fuel tankers, more military vehicles

destroyed.

What I can report from Falluja is that there is no cease fire, and apparently never was. Iraqi

women and children are being shot by American snipers. Over 600 Iraqis have been killed by American

aggression, and the residents have turned two football fields into graveyards. Ambulances are being

shot by the Americans. And now they are preparing to launch a full scale invasion of the city.

All of which is occurring under the guise of catching the people who killed the four Blackwater

Security personnel and hung two of their bodies from a bridge.

April 19, 2004

Cluster Bombs in Falluja, Harrassment of Patients by Soldiers

The word on the street now about why the suicide car bombings have ceased, is that more and more

Iraqis are taking this as proof that the CIA were behind them. Why? Because as one man states, “They are

too busy fighting now, and the unrest they wanted to cause by the bombings is now upon them.” True or not,

it certainly doesn’t bode well for how so many Iraqis are viewing their occupiers nowadays.

Last night I was awakened in the middle of the night by a very large explosion in central Baghdad,

followed promptly by three other smaller explosions.

With so many of the press leaving Iraq, and the majority of those remaining staying close to their

hotels, information about what is truly occurring on the ground here is becoming harder to come by.

For those of us here, it has, needless to say, become increasing difficult to travel around because of

the deteriorating security situation.

Aside from the usual bombs and sporadic gunfire that typifies daily (and nightly) life in the capital

of Iraq today, it continues to be relatively (relative to Baghdad) quiet here. The feeling I get is that

most Iraqis here (aside from those directly fighting the military) are in wait and see mode, their eyes

on Najaf and Falluja.

But this belies the true story, that despite the lack of overt fighting in central Baghdad, the

violence and tension is boiling beneath the surface. On a recent visit to the Arabic Children’s Hospital,

Dr. Waad Edan Louis, who is the Chief Visiting Doctor at the hospital, stated, “Before the invasion, we

had 300 patients per night. Now, we have 100 because the security is so bad.”

Meanwhile, at the Noman Hospital in Al-Adhamiya, a doctor I spoke with there (who asked to remain

nameless) stated, “We are treating an average of one gunshot wound per day, which is something we never

saw before the occupation. This is due to the absence of law in Baghdad. The Iraqi Police have weak

weapons and nobody respects their authority.”

He also stated that U.S. soldiers have come to the hospital asking for information about resistance

fighters. He said, “My policy is not to give my patients to the Americnans, or to provide them any

information. I deny information to the Americans for the sake of the patient. I don’t care what my

patients have done outside the walls of the hospital. I do my job, then let the patient go.”

“Ten days ago this happened-this occurred after people began to come in from Falluja, even though most

of them were children, women and elderly.”

When asked if the U.S. military were bombing civilians in Falluja, he stated, “Of course the Americans

are bombing civilians, along with the revolutionaries. One year ago there was no revolution in Falluja.

But they began searching homes and humiliating people, and this annoyed the people. The people became

angry and demonstrated, then the Americans shot the demonstrators, and this started the revolution in

Falluja. It is the same in Sadr City.”

He continues angrily, “Aggression against civilians has caused all of this. Nothing happened for the