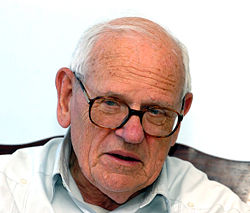

François Houtart

BIOGRAPHY |

PORTRAYING

THE PERSON AND THE WORK OF FRANCOIS HOUTART

| INTERVIEW | INTERVIEW

18 april 2026 |

La messe de François

dans l’île de Fidel

(02 Sept. 2026) |

Socialism for the 21st century.

Synthetic

Framework for Reflection

(François Houtart, 30 August

2006) |

De armoede was

vroeger beter verdeeld

(15 Jan 2026) |

Speech at the General Assembly of the United Nations

(30 Oct

2008) |

BIOGRAPHY |

PORTRAYING

THE PERSON AND THE WORK OF FRANCOIS HOUTART

| INTERVIEW | INTERVIEW

18 april 2026 |

La messe de François

dans l’île de Fidel

(02 Sept. 2026) |

Socialism for the 21st century.

Synthetic

Framework for Reflection

(François Houtart, 30 August

2006) |

De armoede was

vroeger beter verdeeld

(15 Jan 2026) |

Speech at the General Assembly of the United Nations

(30 Oct

2008) |

|

Spanish Biography - Biographie en français |

François Houtart est directeur du Centre Tricontinental (Cetri), dont l’objet est de « faire connaître le point de vue du Sud dans le contexte actuel de mondialisation, de diffuser les propositions d’alternatives, élaborées par le Sud, et de contribuer à une réflexion de fond en rapport avec les mouvements sociaux. »

Après une formation en philosophie et en théologie au Séminaire de Malines, il fut ordonné prêtre en 1949. Licencié en Sciences Politiques et Sociales de l’Université Catholique de Louvain et diplômé de l’Institut Supérieur International d’Urbanisme Appliqué de Bruxelles, François Houtart est l’auteur de nombreuses publications en matière de recherches socio-religieuses et a participé, comme expert, aux travaux du concile Vatican II (1962-1965).

François Houtart est membre du Comité International du Forum Social Mondial de Porto Alegre, Secrétaire exécutif du Forum Mondial des Alternatives et Président de la Ligue Internationale pour les Droits et la Libération des Peuples.

Personnalité incontournable des mouvements altermondialistes, il a participé à de très nombreux ouvrages sur la mondialisation, les luttes sociales et collabore régulièrement avec le Monde Diplomatique.

François Houtart es profesor emérito de la Universidad Católica de Lovaina. Nació en Bruselas en 1925, obtuvo el doctorado en Sociología en la Universidad Católica de Lovaina. Ha sido profesor visitante en diversas universidades del mundo y sus publicaciones incluyen un importante número de artículos y libros. Notre Dame University le otorgó el doctorado Honoris causa y actualmente es director del Centre Tricontinental en donde edita la prestigiosa revista Alternatives Sud.

François Houtart. Belgian Marxist Priest and sociologist, director of the CETRI ( Tricontinental Center ) and the review " Alternatives Sud". Militant antiglobalist. The canon François Houtart is a catholic priest and intellectual Marxist of international fame. Grandson of the count Henry Carton de Wiart (1869-1951), who was one of the leaders of the Catholic Party and pioneer of the Christian democracy, François Houtart was born in Brussels in 1925. After his training in philosophy and theology at the Seminar in Mechelen, he was ordered priest in 1949. Graduated in political and social sciences of the catholic University of Leuven and graduate of the International Higher Institute of Town planning of Brussels , he is a doctor of sociology of the UCL where he was a professor of 1958 to 1990. Author or co-author of many publications regarding socio-religious research, he took part, as expert, in the council of the Vatican II (1962-1965). He participated in the Bertrand Russell War Crimes Tribunal on US Crimes in Vietnam in 1967. Today, he directs a ONG, the CETRI ( Tricontinental Center ) based in Louvain-la-Neuve as well as the review "Alternatives Sud". Regarded as a prophet by the ones, like a dangerous activist by the others, François Houtart is one of the most active collaborators of the World Social Forum of Porto Allegre and one of the most convinced militants for "another globalisation". Houtart is Executive Secretary of the Alternative World Forum, President of the International League for rights and liberation of people, president of the BRussells Tribunal and senior adviser to the President of the United Nations General Assembly Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann.

See biography in Wikipedia: http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fran%C3%A7ois_Houtart (Dutch) - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fran%C3%A7ois_Houtart (English)

François Houtart: De utopie als tegengif tegen de erfzonde

Directeur van het CETRI, Voorzitter van het Wereldforum voor Alternatieven en lid van het organiserend comité van het Mondiaal Sociaal Forum van Porto Alegre.

Priester-socioloog François Houtart heeft er straks een halve eeuw engagement opzitten. Het verwerpen van de utopie als motor voor maatschappelijke veranderingen ziet hij als een intellectuele knieval voor een oppermachtig economisch systeem. Toch weet hij dat een utopie maar nuttig is als ze niet gerealiseerd wordt.

De biografie van François Houtart leest als een catalogus van politieke dromen en grote maatschappelijke omwentelingen. Hij wou eigenlijk missionaris worden. De wereld intrekken, de armen dienen. Maar zijn vader wou dat hij dichter bij huis bleef en dus werd hij seminarist in Mechelen. Enkele jaren later brak de Tweede Wereldoorlog uit en geraakte hij betrokken bij het verzet. 'We deden bruggen springen in de omgeving van Brussel.' Maar zijn echte doop kreeg hij in de KAJ. In 1953 woonde hij een internationaal congres bij in Havana en kardinaal Cardijn vroeg hem om aalmoezenier te worden van de internationale KAJ. Zijn eigen kardinaal, Van Roey, weigerde. Als socioloog bestudeerde hij de vervreemding tussen kerk en arbeiders, die in Europa pijnlijk zichtbaar werd. Het was ook als socioloog dat hij meer en meer betrokken geraakte bij de sociale problemen van Latijns-Amerika. Op vraag van onder andere Dom Helder Câmara werd hij vier jaar lang raadgever van de Latijns-Amerikaanse bisschoppen op het Tweede Vaticaans Concilie. In het zog van het enthousiasme dat daar ontstond voor de rol van de leken in de kerk en voor de rol van de kerk in de samenleving bleef hij ondersteunend werk leveren voor de Latijns-Amerikaanse kerk. Het ontstaan en het opbloeien van bevrijdingstheologie en basisgemeenschappen: hij was erbij. De volksbewegingen en de revoluties in Midden-Amerika: hij volgde ze op de voet. Boerenbewegingen en indiaanse opstanden, syndicaten en catechisten: hij kent ze bij naam en toenaam.

Wie zoveel jaren gestreden heeft, zag meer idealen teloor gaan dan hij er oorspronkelijk

had. Toch tref je bij Houtart geen diepe twijfel aan over de mens of over de utopie. 'Als socioloog wéét ik

dat de kloof tussen de utopie en de menselijke realiteit zal bestaan zolang de mensheid menselijk is.

Anderzijds ben ik er van overtuigd dat mensen de tegenstelling tussen droom en werkelijkheid altijd weer

proberen te verkleinen. Als gelovige zie ik mislukkingen dan ook niet als uitingen van menselijk falen, maar

als uitingen van menselijk pogen. De religieuze ervaring daagt een mens immers uit om méér te doen dan het

haalbare, om méér te verwachten dan het gewone en vooral om menselijker te worden dan hij op eigen krachten

kan.'

Toch weegt de mislukking van een zeer aardse utopie -die van het socialisme- zwaar op

de motivatie van mensen om zich politiek te engageren.

Je moet een onderscheid maken tussen enerzijds de -juiste- vaststelling dat het marxisme als analyse-instrument en het socialisme als utopie niet meer de aantrekkingskracht hebben van vroeger en anderzijds de -vaak miskende- vaststelling dat de realiteit niet fundamenteel veranderd is. De klassenstructuur van de samenleving is niet verdwenen, integendeel, op veel plaatsen in de wereld is die de afgelopen jaren alleen maar scherper geworden. De werkelijkheid blijft bestaan, ook als het bewustzijn verdwijnt. Sterker nog: het is de realiteit met haar steeds verder schrijdende, economische individualisering en met haar toegenomen onzekerheid voor mensen die onderaan de sociale ladder staan, die verantwoordelijk is voor het verdwijnen van een meer sociaal bewustzijn. Mensen zien zich vandaag minder als een deel van een sociale groep dan als een individu of als een deel van een kleine familie. Het is niet meer zo duidelijk waartégen men moet vechten. En het is nog minder klaar waarvóór men zou vechten. Ik denk dat het verdwijnen van de utopie verklaard kan worden door het feit dat de utopieën van de jaren zestig of zeventig té utopisch waren.

Ze waren te mooi om waar te zijn?

Ze waren vooral te haastig. Men dacht dat de Grote Droom gerealiseerd kon worden op korte termijn, terwijl een echt fundamentele verandering van een maatschappij verschillende generaties duurt. In de jaren negentig heeft men dan het kind met het badwater weggegooid. Elke globale toekomstvisie werd verdacht gemaakt. 'De utopie is dood, leve het pragmatisme' werd de slogan. Ik ben het daarmee niet eens. Er is namelijk één grote, wereldomvattende beweging bezig haar ideaal op een succesvolle manier te verwezenlijken: het kapitalisme. Met alle nieuwe technologieën en communicatiemiddelen slaagt het kapitalisme erin om een mondiaal systeem te worden. Niet dat er daartegen geen verzet is: over de hele wereld zie je sociale strijd. Maar die strijd is volkomen gefragmenteerd. Dat komt het zich ontwikkelende wereldkapitalisme mooi uit, natuurlijk. Die verbrokkeling wordt bovendien filosofisch onderbouwd door het postmodernisme in de sociale wetenschappen. Dat postmodernisme stelt dat er geen globale systemen bestaan en dat het gevaarlijk is om een sociale utopie na te streven. Daarmee ontneemt men de mensen die lijden onder het reëel bestaande kapitalisme één van de belangrijkste instrumenten om zich te ontdoen van hun verdrukking.

Niet de utopieën zijn gevaarlijk, maar het verdwijnen ervan?

Een utopie kan wel degelijk gevaarlijk zijn. Zodra men denkt dat ze hier, op aarde gerealiseerd kan worden, gaat het fout. Dat geldt niet alleen voor de sociale utopieën van de laatste eeuwen, maar ook voor veel religieuze bewegingen sinds de dertiende eeuw. Telkens mensen het Nieuwe Jeruzalem op aarde wilden installeren, is dat in een catastrofe geëindigd. Wie gelooft het patent te hebben op een perfect maatschappelijk systeem, die zal altijd weer een inquisitie nodig hebben om halsstarrige zondaars, ketters of ongelovigen te berechten. Ik benader een utopie niet als een gestolde en voor eeuwig vastgelegde waarheid, maar als een dynamisch gegeven. Als het enige tegengif dat echt werkt tegen de erfzonde van onverschilligheid en onrechtvaardigheid. Een utopie is echter enkel geloofwaardig als ze opgebouwd wordt en dus ook bijgesteld kan worden. Als ze verstart tot een dogma, heeft ze geen betekenis meer. Er wordt momenteel een nieuwe, levende utopie opgebouwd door het uitbouwen van netwerken waarin basisbewegingen uit Noord en Zuid, uit Oost en West elkaar vinden en tot onderlinge uitwisseling kunnen komen.

Maken de culturele verschillen het niet onmogelijk om één, globale utopie uit werken?

De beweging die momenteel aandacht vraagt voor de culturele verschillen tussen mensen en volkeren brengt inderdaad een zeer terechte kritiek uit op het feit dat wij te uitsluitend westers geïnspireerde modellen voor ogen hadden. Verschillende volkeren hebben nu eenmaal verschillende visies op de manier waarop mensen met elkaar verbonden zijn en op hun relatie met natuur en bovennatuur. Die diversiteit moet een plaats krijgen bij het opbouwen van een wereldwijde utopie. Maar er zijn ook gevaren aan het benadrukken van de culturele verschillen. Op de eerste plaats mag men niet de fout maken om van cultuur een vastgelegd gegeven te maken. Een cultuur is altijd een dynamisch geheel van ontwikkelingen. Wie dat ontkent, voedt het fundamentalisme -dat is ook een utopie, maar dan een averechtse. Ten tweede mag de aandacht voor culturele diversiteit geen scherm zijn waarachter de economische én culturele overheersing door een globaliserend kapitalisme zich kan verschuilen. Ook de Haïtiaanse voodoocultuur bevindt zich in een wereld vol kapitalistische verhoudingen en producten. Daarmee onvoldoende rekening houden, ondermijnt juist de kansen van de Haïtianen om een eigen toekomstproject op te zetten.

Speelt religie een rol in de opbouw van een nieuwe utopie?

De Mexicaanse staatsuniversiteit -een zéér gelaïciseerd instituut- heeft daarover vorig jaar een seminarie georganiseerd. Het was een zeer interessante ontmoeting tussen gelovigen van allerlei afkomst. De gemeenschappelijke visie van de deelnemers was dat de godsdiensten een onvervangbare aanbreng zullen hebben in de volgende eeuw, op de eerste plaats op het vlak van de ethiek. Ook het herstellen van de symbolen leek ons een belangrijke taak voor de godsdiensten. Want het bestaan van authentieke, menselijke symbolen wordt vandaag bedreigd door het feit dat ze binnen een commerciële context geplaatst worden. Zo worden symbolen uitgehold, opgebruikt en weggeworpen. Religie zal in de toekomst zeer belangrijk zijn, tenminste als ze weerstaat aan de verleiding van de spirituele terugtrekkingsbeweging. De wereld wordt door heel veel mensen ervaren als een ontmenselijkende plek waaraan ze zelf niet kunnen ontsnappen en dus kiezen ze voor een godsdienst die daar helemaal buiten gaat staan. Maar op die manier verliest die zogenaamde 'pure religie' haar humaniserende kracht. De mooiste symbolen uit onze christelijke traditie verwijzen juist naar de mogelijkheid om de wereld mooier te maken. Een plek waar de leeuw en het lam samenliggen. Een plek waar de heersers van hun troon gestoten worden. Een plek waar mensen in staat zijn om zelfs hun vijanden lief te hebben. Zolang de religieuze ervaring en de symbolische weergave ervan niet gedogmatiseerd worden, blijven ze de krachtigste utopie. Een geloof dat doden tot leven kan wekken.

Interview de François Houtard, président du Brussells Tribunal. A.F : Quel sens donnez-vous à la juridiction que vous présidez- certes comme vous

avez vous-même défini au départ quelle nétait non pas illégale, mais non fondée sur un texte juridique-

pouvez-vous nous préciser sa fonction ?

M.H.: Oui en effet, le tribunal na pas de possibilités de sanctions, même

sil peut parfois sappuyer sur le droit international pour donner certains avis. Le but est dalerter lopinion

publique sur un problème fondamental qui importe à lhumanité aujourdhui. Il sagit donc dune fonction

politique et à la fois éthique.

Le problème de lIrak nous apparaît comme central car nous le vivons -le peuple irakien est

en train de le vivre de façon quotidienne et ce problème sont évidemment plus large que lIrak puisque sont

impliquée toutes une série de nations, de pays, de puissances. Et que les victimes sont essentiellement des

victimes irakiennes !

La spécificité de ce tribunal- qui suite à la session du tribunal Russel de 1967 sur les

crimes de guerre au Vietnam, ainsi qua dautres nombreuses sessions dont notamment celle du tribunal permanent

des peuples a linitiative dEllio Basso (un sénateur italien qui était lui-même un des membres du tribunal

Russel) qui a produit au moins une trentaine de sessions sur différents sujets concernant le Nicaragua, les

Philippines ou encore la banque mondiale et le fond monétaire international- est de replacer le problème de

lIrak dans tout un ensemble et de montrer que lIrak nest quun incident à lintérieur dune politique plus

fondamental.

Aussi, ce qui est en jeu dans notre tribunal, cest danalyser le PNAC : le programme pour un

nouveau siècle américain. Il sagit dun document qui a été élaboré en 1997 par des milieux néoconservateurs,

à savoir, un petit groupe essentiellement formé dintellectuels très intégrés dans les grandes

multinationales américaines qui a essayé de repenser toute la poltique américaine pour lui donner un

certain impact sur lhistoire du monde daujourdhui. Ce que nous constatons également cest que cela va plus loin que la logique que poursuit ce

petit groupe arrivé au pouvoir avec le président Bush aujourdhui. Lorsque nous analysons les positions du

candidat président Kerry et les politiques qui sont menées par les démocrates dans le passé, cela nous amène

à dire que le problème ne résulte pas seulement dun petit groupe qui pense de façon fondamentaliste, mais

quil sagit là dune logique politique qui reflète une longue tradition dans lhistoire des Etats- Unis. Et

que cette dune logique politique est liée à une logique économique donc à une domination économique.Et

que tout ce qui est produit comme justification morale ou idéologique a également un lien logique avec tout

cet ensemble dintérêt économique et politique. Nous nous retrouvons donc véritablement devant un empire -

nous ne sommes pas anti-américain, je lai dit à linauguration de ce tribunal.en aucune façon. La preuve

cest quil y a beaucoup daméricain, ici présents, à ce tribunal, parmis les témoins, parmi les membres de

la commission ou de la défense. Ce qui est donc est en jeu, ce nest pas le fait dêtre américain, cest le

fait dêtre hégémonique, cest la fait dêtre un empire et aujourdhui au vingt et unième siècle, lempire

est américain !

Cest cela que nous voulons dénoncer, avec toutes les conséquences que ca a peut avoir et

ainsi pouvoir alerter une opinion publique qui bien sur est de plus en plus consciente de ce que cest lIrak

et de plus en plus opposée à la continuation de la guerre en Irak mais qui nest as toujours consciente des

tenants et aboutissants de ce quest et a été la guerre en Irak aujourdhui.

A.T : Aujourdhui, on est peut-être a la fois optimiste et un pessimiste face à

limperium américain : Un pessismisme ressentit vis-à-vis de limperium américain et un optimisme face à

une prise de conscience collective. jentends par-là que le monde sest réjoui par exemple à la destruction

du mur de Berlin et on a ainsi détruit avec le bipolarisme des nations comme contexte

international.aujourdhui on se retrouve face à une super puissance hégémonique. Faut-il penser que le

temps - puisquil faut donner le temps au temps, selon un vieux proverbe portugais- nous permettra de voir lémanation

démocratique de la conscience démocratique populaire?

Je crois quil faut être évidemment optimiste sinon on ne croit plus dans lhumanité. Mais

ne pensons que le temps se fait tout seul. Par conséquent, il y a un engagement à avoir. Lhistoire navance

pas comme un long fleuve tranquilleelle est toujours le résultat dun certain nombre de luttes sociales et

cest dans la mesure où cest luttes sociales vont véritablement pouvoir sexprimer et créer tout doucement

et le plus rapidement possible, bien sur, un autre pole de force par rapport au pole qui est aujourdhui dominé

par le capital international et par le caractère hégémonique de la politique américaine. Cest dans cette

mesure où nous pourrons construire cest autre pole, où nous pourrons alors véritablement croire dans nos

espérances. Sans cela, elles resteront purement symboliques.

Tout ce que lon voit aujourdhui permet déveiller une espérance, de la garder vivante. Cest

que lon a vu au forum social mondial auquel j'ai participé, qui était fort impressionnant par ailleurs. Il

y a là une force nouvelle qui est en train de se construire, peut-être difficilement parce que très hétérogène,

mais qui se construit comme une conscience collective mondiale face à un système qui reste éminemment

puissant. Ce système a en main beaucoup de moyen pour essayer détruire ce mouvement, cette réaction

populaire, mais je pense quil est néanmoins obligé den tenir compte aujourdhui et cest déjà quelque

chose.

Je résumerai en disant simplement ceci : « lespoir nous ne devons jamais le perdre et nous

devons construire un autre type de société ». Mais cela naura de résultat que dans la mesure où cette résistance

peut sorganiser, peut avoir les instruments pour pouvoir être efficace.

Cette conscience collective peut-elle avoir une influence sur lestablishment actuelle et

quelles en seraient les conséquences économiques, la vision que lon pourrait avoir ?

Je crois que vous poser là tout le problème des alternatifs. Est-quil y a des alternatives

à la situation actuelle au marché capitaliste, à ce quon appelle la démocratie parlementaire qui est

encore fort limité comme nous le savons. Il y a aussi des alternatives qui sont proposées sur un plan concret, cest à dire, à

moyen terme: quest ce que nous pouvons faire ? A court terme : Est-ce que nous pouvons établir une taxe

Tobin pour limiter limportance du capital financierbien sur cela ne va pas encore détruire le capitalisme

mais cest malgré tout un pas en avant ? Est-ce que nous pouvons supprimer les paradis fiscaux? Est-ce que

nous pouvons décider dabolir la dette du tiers-monde? Il y a là toute une série dalternatives qui existent

mais ce qui manque cest la volonté politique de les appliquer. Regardez on a essayé de faire quelque chose et regardez ce qui sest passé dans les pays

socialistes avec le socialisme réel, est-cela une alternative? Bien sur, il y a eu un échec et nous devons

étudier et analyser les causes de léchec pour nous rendre compte pourquoi il y a eu échec, pour des

raisons internes et pour externes.

Le problème nest pas quil nait pas dalternatives, le problème cest quil ny a pas de volonté

politique pour les appliquer. Doù la nécessité de créer une pression populaire qui puisse faire pression

sur les décideurs politiques et voir ainsi voir se réaliser les alternatives et arriver réellement à

construire. Cest un processus permanent ces utopies et les alternatives ne tombent pas du ciel Cela doit être

construit et construit collectivement. Et par ailleurs ce nest pas non plus le royaume de dieu que nous

construisons sur terre simplement parce que lon a fait une révolution ou parce quon a changé un système

politique, cest un processus constant qui va de la vie quotidienne aux grandes décisions de macroéconomie

ou de macropolitique.

La révolution permanente où il faut sans cesse se remettre en cause, nous sommes très

loin des grands philosophes et grands utopistes de la révolution de 1989 ( chute du mur de Berlin) et celles

qui ont suivi par le monde. Aujourdhui la vrai révolution ne serait pas que les citoyens-électeurs invitent

ceux qui ont des mandates à rendre des comptes plus précis?

Bien sur, cest un des mécanismes fondamentaux et qui existe relativement peu dans nos sociétés

démocratiques. Je suis frappe de voire, peut-être que lexemple risqué dêtre mal compris, travaillant

beaucoup à Cuba, je me rends compte que cest un mécanisme qui fonctionne. Je ne dis pas que Cuba est une démocratie

parfaite- pas beaucoup moins que les nôtres- il est un fait néanmoins que les délégués au parlement

cubain doivent rendre compte tous les six mois devant des assemblées populaires. Cela fonctionne, c-à-d, qu

on leur demande : pourquoi avez-vous fait telle chose ou pourquoi ne lavez pas vous pas fait. Ils sont

constamment soumis à ce mécanisme. Je penses que lon pourrait sinspirer de cela dans nos démocraties pour

pouvoir avoir un fonctionnement plus souple et beaucoup plus réel de la démocratie.

Ceci dit, cest évidemment la démocratie qui est le moyen , non seulement la fin , mais le

moyen fondamental pour pouvoir transformer nos sociétés en démocratie réelles, fondamentales, qui ne se résumeraient

pas simplement au fait délire des personnes tous les quatre ans.. Cela est le respect de la démocratie qui

certes nous paraît incontournable aujourdhui, mais qui nest qune petite partie de ce qu est vraiment la démocratie.

Où se trouve la démocratie dans notre système économique par exemple? Où se trouvent

aussi les possibilités dune démocratie plus participative, plus quotidienne? Nous avons certainement de

grandes améliorations à apporter.

Y.B : . Et de quelle façon compter vous réagir face aux dernières propositions de

ladministration Bush ? Après avoir tenté de légitimer ses actions sous le couvert des droits de lhomme,

elle désire aujourdhui les faire valoir sous le drapeau du développement et de présenter au prochain G8 un

document de travail intitulé Partenariat G8 et Moyen Orient »

La réponse est catégorique, cest non! Il nest pas question que l « on » puisse accepter

une telle proposition comme semble lindiquer aujourdhui Kofi Annan ou peut-être même Louis Michel. Il nest

pas question daccepter quelques solutions que ce soit tant que les américains seront là, et par conséquent,

cest la condition fondamentale et tout compromis avec les américains dans ce domaine là me parait comme une

manière de prolonger le problème et par conséquent de prolonger la situation de guerre , de violence et de

terrorisme.

Il faut , je crois, être extrêmement clair et il faut comme cela sera encore souligné au

Brussel Tribunal, il faut laisser la possibilité aux irakiens de prendre une initiative quitte à ce quelle

soit appuyer par une communauté internationale mais dans des limites absolument légales et respectant la

souveraineté de lirak.

Cest facile aujourdhui pour les américains de dire, oui, aujourdhui, on a cassé la

baraque, il faut bien essayer de la reconstruire, et nous ne sommes peut-être pas les mieux placés pour le

faire, venez nous aider. Cest cela quil faut absolument dénoncer et refuser parce que on va nous faire

beaucoup de propagande et de publicité pour dire : voyez-vous, nous sommes gentils, nous voulons aider les

irakiens à se reconstruire, mettons nous tous ensemble, ne pensons plus au passé, abandonnons les querelles

de familles que nous avons eu précédemment et joignons nous tous ensemble pour reconstruire lIrak. cest

dune hypocrisie absolument incroyable. Je crois que là, nous devons être radicaux et dire non, ce nest pas

cela que nous voulons, nous avons des alternatives à proposer.

Y.B : Mais ne craignez-vous pas que les membres du G8 sur le terrain du développement

et de léconomie accepteront la nouvelle proposition de Bush and corporated?

F.H : Cest bien la raison pour laquelle, nous devons aussi protester contre le G8. A Gênes,

les grandes manifestations, cétaient contre le G8, il nous apparaît comme un instrument de lhégémonie

dans le monde. Certains de ceux qui y sont présents sont obligés de faire des concessions pour garder un

certain ordre dans ce quils peuvent contrôler mais rappelons que le G8 nest pas un organe démocratique, ni

représentatif de lhumanité.

Y.B/Pensez-vous que le développement dune zone de libre échange au Moyen-Orient

puisse représenter une alternative à lhégémonie américaine ?

F.H :Ces zones de libre-échange, cest la grande politique américaine. Je peux la résumer

en quelques mots : « Ce sont les accords entre le requin et les sardines » car le libre commerce signifie

la possibilité pour le plus fort dimposer sa loi. Cest ça finalement qui est en jeu.

Certainement quà lintérieur de certains pays, quelques-uns y verront un avantage parce que

certains secteurs de léconomie locale peuvent avoir un avantage à pénétrer le marché nord américain,

mais cet avantage nexiste que pour une toute petite partie des intérêts économiques des pays concernés.

Cest donc un marché de dupe mais qui est souvent appuyé par les pouvoirs politiques qui existent dans ces

pays là parce quils représentent ces secteurs dintérêt économique local et qui abondamment répandent

une propagande, une idéologie qui se base sur la liberté et ainsi la liberté de commercer. Ils tirent

ainsi avantage de ce pacte où tout le monde est gagnant, comme on dit au USA, une solution « win win ».

Mais cest une illusion totale.

Y.B :Et sil sagit dune proposition régionale prise à linitiative des pays arabes

pour un développement endogène ?

F.H :Cest autre chose, si les pays arabes désirent de leurs propres initiatives faire un

marché d échanges comme le Mercosur ou lEurope, cest bien entendu un pas positif mais à condition quil y

ait une autonomie de décision, que cela ne soit pas imposé de lextérieur, et que finalement cela ne soit

pas simplement une autre manière de réaliser la globalisation du capitalisme. Puisque qu actuellement la

globalisation fonctionne mal sur un plan totalement global, sa relance pourrait sappuyer sur des créations

de noyaux régionaux capitalistes.

Je crois que nous devons être en faveur des regroupements régionaux sur un plan économique

mais en veillant à ce que leurs finalités dépassent la logique capitaliste pour mieux répondre aux

besoins des populations et des gens.

http://www.indymedia.be/news/2004/04/83568.html

La messe de François dans l’île de Fidel

GIANNI MINÁ

Le rendez-vous à l’église de San Agustin est à sept heures et demie. Le vieux

François allait dire la messe pour fêter monseigneur Carlos Manuel De Cespades, descendant du père de la

patrie cubaine et curé de cette église, qui revient après une cure en Suisse pour lutter contre une maladie

insidieuse. François Houtart, quatre vingt deux ans, prêtre du clergé séculier, enseignant de sociologie

pendant des années à l’université de Louvain en Belgique, a été parmi les concepteurs et les fondateurs du

Forum social de Porto Alegre. Il est à La Havane avec d’autres intellectuels pour la réunion du mouvement

En défense de l’humanité, qui a eu son baptême à Caracas en décembre 2026, comme je l’ai dit dans un

autre article; et qui tiendra une autre session à Rome, à la Fao, en octobre. Ce religieux qui, dans sa

jeunesse, a enseigné aussi la sociologie à Hanoi, sous les bombes des B-52 étasuniens, obligeant la rigide

organisation du parti communiste local à se confronter avec la dialectique des sciences sociales, s’est

senti offensé par la manière dont on a traité dans l’information, depuis le 31 juillet, la maladie de Fidel

Castro ; et plus encore, il s’est indigné pour le plan sur l’avenir de Cuba, décidé de façon désinvolte par

le Département d’Etat américain, et renouvelé en toute occasion par Bush et Rice.

La souveraineté de Cuba

C’est pour cela qu’il a rendu public, lundi 5 août, un manifeste intitulé « La

souveraineté de Cuba doit être respectée » qui, en quelques jours, a été signé par plus de dix

mille intellectuels du monde entier dont neuf prix Nobel. François en a discuté avec Raul Suarez, pasteur

protestant, président du Conseil des églises œcuméniques de Cuba, il veut en parler à Carlos Manuel De

Cespades, avec Frei Betto, présent lui aussi à La Havane, et qui était avec François quand, après la visite

de Jean Paul II en 98, Fidel Castro invita quatre théologiens de renommée mondiale pour interpréter, de

l’intérieur, les sept homélies prononcées par Pape Wotjyla dans l’île.

La rencontre dans la sacristie de San Agustin est affectueuse. Carlos Manuel,

par sa famille, est aussi descendant du général Menotte, dit el majoral, président du pays au début

du siècle dernier, et qui accepta définitivement la tutelle du gouvernement de Washington dans la vie

politique de la nation, a eu une jeunesse de militance catholique opposée au nouveau régime socialiste ; il

a même fait l’expérience pendant quelques semaines d’un camp de travail, mais ne s’est jamais perdu entre

les excès de la Revolucion et l’intolérable siège politique et économique, parfois terroriste, des

Etats-Unis. En 97, quand il était porte parole de l’actuel cardinal de La Havane, à l’époque archevêque,

Jaime Ortega y Alamino, il commenta d’une phrase drastique, « ces bombes viennent de Miami », la

prolifération soudaine des attentats contre des installations touristiques de l’île. L’évêque de la ville

symbole de la Floride s’en émut fortement et demanda une intervention à son collègue de La Havane, qui

imposa le silence à son porte parole jusqu’à la fin du voyage papal en janvier 98. Maintenant, après la

confession et la condamnation de Ernesto Cruz-Leon, auteur matériel des attentats dans l’un desquels mourut

Fabio Di Celmo, nous savons que le mandant de ce terrorisme était la Fondation cubaine américaine de

Miami : sous la direction de Luis Posada Carriles, le Ben Laden latino-américain, dont le gouvernement des

Etats-Unis n’a pas encore décidé de ce qu’il va faire, l’extrader dans un pays complaisant ou, enfin, le

juger. Souvenir qui, de nos jours encore, est plus effrayant qu’affligeant. François Houtart, qui a rendu

visite à l’archevêque la veille, commente avec un peu d’ironie : l’ami Jaime « se suavizo » (s’est

radouci) et observe maintenant la révolution sans préjudice « en cohérence avec l’esprit de l’évangile ». Il

n’est donc pas surpris que l’église de Rome, sensibilisée par la Curie de La Havane, ait demandé justement

ces jours ci de prier pour Fidel, provoquant l’indignation des catholiques réactionnaires de Floride et

d’Amérique Latine, « si proches de l’argent et si loin de Dieu ». François qui, à 37 ans à peine, au Concile

de Vatican II entra comme expert dans une commission de recherche sociale dont faisait aussi partie Karol

Wotjyla, confirme ainsi sa franchise, et le prestige qui, à Porto Alegre en 2026, lui fit demander au

président Lula, de façon très explicite et hors de tout schéma, les raisons du retard, au Brésil, du

changement social tant attendu qui, deux ans après son élection, avançait encore au ralenti en regard des

promesses faites pendant sa campagne électorale.

« Beaucoup de choses se sont améliorées dans les rapports entre le Vatican et

Cuba après la visite de Jean Paul II » remarque Carlos Manuel De Cespades, et il se souvient avec affection

que cette évolution a commencé vers la moitié des années 80, grâce à l’engagement de Frei Betto, après son

livre interview Fidel et la religion, pour rompre l’incommunicabilité et favoriser le dialogue entre

la révolution et le clergé local. Dialogue qui, ensuite, a continué de façon autonome. Pour la première

fois, l’église cubaine a rejeté le blocus économique imposé à l’île par les Etats-Unis, et le gouvernement

de La Havane a effacé l’athéisme de sa constitution pour le remplacer par le concept de laïcisme. Il n’est

donc pas surprenant que, même en 2026, après qu’aient été fusillé à La Havane trois des onze membres du

groupe qui, armes à la main, avaient assailli le groupe de touristes du ferry boat de la Bahia de Regla,

dans une tentative de détournement, le cardinal Sodano, secrétaire d’état, ait déclaré « l’Eglise continue à

avoir confiance dans le gouvernement de La Havane pour conduire Cuba vers une démocratie accomplie ».

Déclaration qui, à l’époque, eut le mérite d’imposer une réflexion plus profonde sur les méthodes de siège

étasunien contre Cuba, et sur les conséquences néfastes que cette politique incorrecte pouvait avoir sur la

façon de réagir de la révolution.

Les nouveaux séminaires

Il n’y a pas eu que des inaugurations de nouveaux séminaires et lieux de culte,

dans l’île, et constructions de centres d’attention sociale de l’église catholique, comme ceux de la

Communauté de San Egidio et des sœurs Brigidines ; les moments de rencontre entre les différentes religions

et la révolution sont aussi devenus plus clairs et fréquents. L’église catholique, en particulier, a accru

sa présence dans la vie du pays même dans ce secteur sanitaire où Cuba est un exemple pour tout le

continent, avec ses trente mille médecins travaillant dans de nombreux pays socialement atteints, comme

Haïti, l’Angola, le Pakistan. C’est sur ce terrain que s’est développée une entente entre le Vatican et

Cuba, qui amène le pape Ratzinger à être plus généreux, dan ses voeux de bonne santé à Fidel, que Pietro

Ingrao. Et qui a poussé le collègue Cotroneo, dans le Corriere della Sera, à délirer sur une présumée

« conversion » du leader maximo.

Le livre de Ramonet

L’infirmité de Fidel Castro a mis d’abord en crise les délais de la réédition

du livre Cento ore con Fidel, d’Ignacio Ramonet, (publié en Espagne sous le titre Fidel Castro :

biographie à deux voix) et prochainement édité en France, Angleterre, Italie, Allemagne, Etats-Unis,

Canada, Mexique, Argentine, Brésil, Colombie, Venezuela, et jusqu’au Japon et en Chine. La première édition,

immédiatement épuisée à Cuba et en Espagne, où elle était sortie en mai, avait cependant suggéré à Fidel

quelques ajouts, augmentations, précisions, qu’il apportait aux épreuves lorsqu’il a été contraint à cette

intervention immédiate pour sa désormais fameuse papillome à l’estomac.

Le livre du prestigieux directeur du Monde Diplomatique, fruit de

plusieurs rencontres au cours de trois années, suit, deux décennies plus tard, de façon encore plus large

(633 pages, avec 70 pages de notes et index) la trace du récit que Castro me fit pour deux documentaires

devenus historiques, en 87 et en 90, transcrits ensuite dans deux publications. Le travail fait avec Ramonet

est une sorte d’autobiographie, un bilan de sa propre vie publique plus que privée, au seuil des quatre

vingt ans, quand on peut se risquer aussi à des révélations inédites, des jugements hors toute diplomatie,

aux autocritiques, et aux confidences.

Saint Ignace de Loyola

Ramonet, comme je le fis à l’époque, tout en rappelant dans son introduction

les agressions constantes que Cuba subit de l’extérieur, et citant même Saint Ignace de Loyola « dans une

forteresse assiégée toute dissidence est considérée comme une trahison », ne dédouane pas la révolution des

trois cents prisonniers d’opinion qui sont dans ses geoles, et de la peine de mort. Avec une grande

honnêteté intellectuelle, le directeur du Monde Diplomatique ne néglige pas de rappeler cependant que

la peine de mort abolie dans la majorité des pays évolués est toujours en vigueur, en plus de Cuba, aux

Etats-Unis et au Japon ; et il souligne aussi comment, dans ses rapports critiques, Amnesty International ne

signale pas à Cuba de cas de torture physique, de desaparecidos, d’assassinats politiques et

escadrons de la mort, de manifestations réprimées par la violence de la force publique, au contraire, par

exemple, d’états de ce même continent sud-américain considérés comme « démocratiques », tels que le

Guatemala, le Honduras, le Mexique. Sans oublier la Colombie où « sont assassinés impunément syndicalistes,

opposants politiques, journalistes, prêtres, maires, et leaders de la société civile, sans que ces crimes

fréquents ne suscitent une émotion dans le monde des médias internationaux ».

C’est une approche honnête, qui ne justifie aucun manque de libéralité commis

à Cuba mais qui impose une réflexion sur la violation permanente dans le monde, en plus des droits

civiques, des droits économiques, sociaux et culturels, phénomènes inconnus dans l’île. La prompte

récupération physique de Fidel Castro a cependant soulagé de leurs angoisses les éditeurs de la biographie

que le leader maximo n’est pas arrivé, finalement, à écrire, mais qu’il a fait en sorte de laisser à

l’histoire.

Pedro Alvarez Tabio, « l’autre mémoire de Fidel », gardien rigoureux depuis

trente ans du patrimoine littéraire et historique de la révolution cubaine, recevait, depuis le 15 août

déjà, deux chapitres par jour corrigés de la main du commandant convalescent. Ainsi, la deuxième édition

respectera les délais prévus pour la publication. D’aucuns vont jusqu’à jurer que Fidel se présentera lors

d’une des journées entre le 11 et le 16 septembre au Palacio de las Convenciones, pendant le sommet

des Pays non alignés, qui accueillera à La Havane plus de 100 chefs d’état des nations de ce qu’on appelle

tiers monde.

Cet article est la deuxième partie d’une série de deux reportages depuis Cuba

de Gianni Minà, on pourra trouver la première partie, en italien, sur :

Edition de samedi 2 septembre 2026 de il manifesto

Traduit de l’italien par Marie-Ange Patrizio Kan een kanunnik een marxist zijn? Dat kan,

zegt de 81-jarige François Houtart. Hij is het nog altijd allebei. Houtart

is de bezieler van het World Social Forum. Een gesprek met een

oud-strijdmakker van Ho Chi Minh, Dom Helder Camara, Fidel Castro en Jozef

Cardijn. Als het goed is, bevindt François Houtart zich nu in de

Keniaanse hoofdstad Nairobi, waar volgende week het World Social Forum

(WSF) wordt gehouden. Die bijeenkomst van andersglobalisten verwacht opnieuw

tienduizenden deelnemers uit de hele wereld. Kanunnik Houtart ligt mee aan

de basis van het Forum, dat nog altijd een alternatief wil zijn voor het

jaarlijkse World Economic Forum (WEF) in het Zwitserse Davos - de

jaarlijkse hoogmis van het kapitalisme. © Patrick De Spiegelaere Als jongeman reisde Houtart aan de zijde van kardinaal

Jozef Cardijn door Latijns-Amerika. Sindsdien komt hij op voor de armen en

de verdrukten in de wereld. Hij is overigens een kleinzoon van de katholieke

politicus Henri Carton de Wiart, die in de jaren twintig kort eerste

minister was. Als godsdienstsocioloog stelde Houtart zijn engagement later

ter beschikking van bevrijdingsbewegingen in Centraal-Amerika en Indochina.

Hij werd een compagnon de route van Fidel Castro en mocht priesters

die voorgingen in de strijd, zoals Camillo Torres en Ernesto Cardenal,

vrienden noemen. In 1976 richtte hij aan de universiteit van

Louvain-la-Neuve zijn Centre Tri-Continental op om zich over vraagstukken

van de derde wereld te buigen. Bij de twintigste verjaardag van dat centrum,

in 1996, stelde Houtart een bijeenkomst voor die een alternatief moest zijn

voor Davos. Het resultaat was het Forum Mondiale des Alternatives,

dat in januari 1999 in Zürich een ontmoeting organiseerde met vijf grote

sociale bewegingen uit de hele wereld. De Braziliaanse boerenbeweging pikte

het idee op en organiseerde in 2026 een eerste World Social Forum in Porto

Alegre. De organisatoren rekenden op vier, vijfduizend mensen.

Het waren er twintigduizend. Een jaar later kwamen er zestigduizend mensen

op af en daarna honderdduizend. Bij de laatste bijeenkomst in Porto Alegre

waren er 155.000 deelnemers. Het WSF is een instituut geworden, met

gedecentraliseerde fora in de verschillende landen en continenten. Omdat de

organisatie veel te zwaar werd, besliste de internationale raad - waarvan

Houtart nog altijd deel uitmaakt - om het WSF nog slechts om de twee jaar te

organiseren. Dit jaar dus voor het eerst op Afrikaanse bodem, in Nairobi. Krijgt u niet het gevoel dat u daar voor eigen

parochie preekt? FRANCOIS HOUTART: Misschien wel. Maar is dat erg? Het

World Social Forum is een ontmoetingsplaats voor iedereen die de strijd wil

aanbinden met het neoliberalisme: sociale bewegingen, niet-gouvernementele

organisaties en onafhankelijke intellectuelen. Er worden geen beslissingen

genomen, maar ideeën en ervaringen uitgewisseld. Margaret Thatcher zei

destijds: there is no alternative . Intussen begint wereldwijd het

besef door te dringen dat er wél alternatieven zijn voor het neoliberalisme

en dat het mogelijk moet zijn de wereldeconomie op een andere manier te

organiseren. Het World Social Forum heeft daarbij als katalysator gewerkt. De globalisering is niet alleen een probleem voor het

arme zuiden, maar ook voor de geïndustrialiseerde wereld. HOUTART: Men begint zich er rekenschap van te geven dat

de logica overal dezelfde is. De armoede in Europa of de Verenigde Staten

heeft uiteindelijk dezelfde oorzaken als de armoede in de derde wereld. In

Latijns-Amerika en zelfs in sommige Afrikaanse landen hebben zich de

voorbije twintig jaar enorme economische ontwikkelingen voorgedaan. De

steden zijn er in omvang verdubbeld of verdriedubbeld, met overal hetzelfde

beeld: verkeersopstoppingen, wolkenkrabbers, op iedere hoek van de straat

een vier- of vijfsterrenhotel. Maar van de nieuw verworven rijkdom profiteert

uiteindelijk niet meer dan twintig procent van de bevolking. De

middenklassen blijven kwetsbaar en er komen steeds meer armen bij. Dezelfde

mechanismen spelen in het Westen. Kapitalisten slijten hun gesofisticeerde

producten aan twintig procent van de bevolking. Die andere tachtig procent,

die nauwelijks koopkracht heeft, is voor hen niet interessant. Ook communistische regimes, zoals de Chinese

Volksrepubliek of Vietnam, omhelzen de vrije markt. Communisme en

kapitalisme blijken perfect samen te kunnen gaan. HOUTART: Ik las onlangs een rapport van de Wereldbank,

waarin Vietnam een successtory werd genoemd: de armoede zou er zowat

gehalveerd zijn sinds het land tien jaar geleden overgeschakeld is op een

vrijemarkteconomie. Arm is, in de definitie van de Wereldbank, wie minder

dan twee dollar per dag te besteden heeft. Wat het rapport er niet bij

vertelde, was dat onderwijs en gezondheidszorg in Vietnam niet langer gratis

zijn. Meer dan een kwarteeuw geleden heb ik een sociologische

studie gemaakt van een dorp in de delta van de Rode Rivier. Vorige maand ben

ik teruggekeerd naar dat dorp om er na te gaan wat er veranderd is sinds de

invoering van de vrije markt. Wat mij opviel, was dat de overheid kennelijk

niet langer de instrumenten heeft om publieke investeringen op peil te

houden. Irrigatiekanalen worden niet meer onderhouden, coöperaties

ontmanteld. In Hanoi - om over Ho Chi Minhstad nog maar te zwijgen - zie je

steeds grotere tegenstellingen tussen arm en rijk. Was er onder communistische regimes vroeger meer

sociale rechtvaardigheid? HOUTART: Laten we zeggen dat de armoede beter verdeeld

was. Ik zal niet zeggen dat er vroeger geen mensen waren die privileges

hadden, maar je zag geen extreme rijkdom. Nu ontwikkelen topmensen van de

communistische partij zich tot wilde kapitalisten. Kijk maar naar de

zogenaamde Gini-coëfficiënt, die door de Verenigde Naties wordt gebruikt om

inkomensongelijkheid aan te geven: in de Chinese Volksrepubliek is het

verschil tussen de armsten en de rijksten nu haast even groot als in

Latijns-Amerika. Arbeiders in Europa verliezen hun baan omdat arbeiders

in China of India goedkoper zijn. HOUTART: Niet alleen in Europa. Ook uit Sri Lanka, een

land dat ik toevallig goed ken omdat ik mijn doctoraalscriptie heb gemaakt

over het boeddhisme in Sri Lanka, trekken buitenlandse investeerders zich

terug, omdat de arbeidskracht in China of Vietnam bijvoorbeeld nóg goedkoper

is. Wordt op het World Social Forum over dat soort

kwesties gediscussieerd? HOUTART: Zeker. Op het internet circuleren allerlei

voorstellen, die in Nairobi besproken zullen worden. Bijvoorbeeld: wat kun

je doen om te verhinderen dat de export van goedkope Chinese auto's naar

België de sluiting van Volkswagen Vorst tot gevolg heeft? Je zou kunnen

overwegen om een hoge invoerbelasting te heffen, waardoor de

concurrentiepositie van Europese auto's gevrijwaard blijft, en die belasting

vervolgens terugstorten aan de Chinezen om in China het lot van de lokale

arbeiders te verbeteren. Ik besef dat het tamelijk utopisch klinkt, maar we

zullen in ieder geval naar oplossingen moeten blijven zoeken. Is het marxisme als wetenschappelijk instrument

vandaag nog bruikbaar voor een socioloog? HOUTART: Dat denk ik wel. Zou een kanunnik zich een marxist durven noemen?

HOUTART: Natuurlijk. Ik schaam me daar niet voor -

integendeel. Maar ik ben natuurlijk geen dogmatisch marxist. Mijn ervaring

met communisten is dat ze, overal waar ze aan de macht zijn gekomen - in de

Sovjet-Unie, maar ook in Vietnam en zelfs op Cuba - de sociologie hebben

afgeschaft. Communisten gaan ervan uit dat het marxisme op alle vragen het

antwoord heeft. En dan is er vanzelfsprekend geen sociologisch onderzoek

meer nodig. Ze hebben daar een zware prijs voor betaald, want het gevolg is

geweest dat ze totaal blind zijn gebleven voor wat er in de communistische

samenlevingen aan de hand was. Kunnen marxisme en christendom met elkaar worden

verzoend? HOUTART: Het zou een karikatuur zijn om Jezus Christus

een marxist te noemen. Dat was hij natuurlijk niet, maar hij koos wel partij

voor de armen. In dat engagement ligt de basis van zijn boodschap, van het

evangelie, van de waarden die hij in zijn eigen samenleving uitdroeg. Onze

samenlevingen zijn veel complexer geworden. Er is daarom analyse nodig en

het marxisme is, volgens mij, nog altijd het meest adequate instrument om te

begrijpen wat er in de samenleving gebeurt. Marx zei toch dat godsdienst opium is voor het volk?

HOUTART: Ja, maar hij zei ook dat godsdienst zuurstof kan

zijn voor onderdrukte volkeren. Hij zag de dubbele rol die godsdienst kan

spelen. Mijn terrein was dat van de godsdienstsociologie. In de jaren

tachtig praatte ik regelmatig met Cubaanse intellectuelen over de

bevrijdingstheologie in Latijns-Amerika en het engagement van christenen in

revolutionaire bewegingen in El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua. Ze

overtuigden er het centraal comité van de Cubaanse communistische partij van

om me te inviteren voor een stoomcursus voor het topkader. De conclusie was

dat een marxistische benadering niet kan vertrekken van een dogma - dat

godsdienst opium is voor het volk - maar altijd naar de werkelijkheid moet

kijken. Was uw klasje geslaagd voor het examen? HOUTART: Een jaar later schrapte een partijcongres de

paragraaf die gelovigen uitsloot van lidmaatschap. Er speelden daarbij

natuurlijk ook andere overwegingen - het was ten slotte belachelijk. Maar ik

heb ook hier in Leuven altijd de marxistische benadering gebruikt. Ze is

naar mijn mening het meest geschikt om de rol te begrijpen die godsdiensten

in de samenleving spelen. Wanneer hebt u Fidel Castro voor het laatst ontmoet?

HOUTART: Vorig jaar, voor hij ziek werd. Kan het communisme in Cuba na Fidel overleven? HOUTART: Niemand had zich voorgesteld dat het 'post-Fideltijdperk'

al bij zijn leven zou beginnen. Ik was er nog in december. Zijn broer Raúl

heeft veel krediet opgebouwd omdat hij zich discreet opstelt. Discreet en

efficiënt. De vraag is nu of het land de noodzakelijke beslissingen kan

nemen om van een socialisme van de 20e eeuw over te stappen naar een

socialisme van de 21e eeuw en het systeem kan aanpassen zonder de grote

verworvenheden op het vlak van gezondheidszorg, onderwijs en cultuur te

verliezen. Dat wil dus zeggen: zonder de weg op te gaan van China en

Vietnam. Helpt de opmars van links in Latijns-Amerika de

Cubanen om die stap te zetten? HOUTART: Zeker. Maar omgekeerd zou die ontwikkeling

zonder Cuba ook niet mogelijk zijn geweest. De grote onbekende is hoe de

Verenigde Staten zullen reageren. Raúl stelde de Amerikanen een dialoog

voor, maar Bush weigert met hem te praten. Overigens: als het Amerikaanse

embargo van de ene op de andere dag zou worden opgeheven, is dat gevaarlijk

voor de Cubaanse samenleving. De schok van een plotselinge overvloed aan

consumptiegoederen kan te groot zijn. U zat onlangs in Mexico nog een volkstribunaal voor

over de Amerikaanse Cuba-politiek. De traditie van Lelio Basso en Bertrand

Russell ligt u na aan het hart. Maar heeft zo'n namaakrechtbank eigenlijk

wel impact? HOUTART: Het hangt ervan af wat de massamedia ermee doen.

Het zijn natuurlijk opinierechtbanken zonder enige juridische grondslag. Ze

halen hun macht uit hun overtuigingskracht, en daarom moeten ze serieus

werken en moeten de media meewillen. En die laten het afweten? © Patrick De Spiegelaere HOUTART: Soms wel, soms niet. In Bogota werd recent een

tribunaal gehouden over de straffeloosheid van paramilitaire organisaties.

De zitting werd gehouden in het Colombiaanse parlement. Ik zat als

voorzitter van het tribunaal twee dagen in de stoel van de

parlementsvoorzitter. Naast een groot portret van Simon Bolivar. We hoorden

de meest vreselijke getuigenissen uit twee wijken in de stad waar de

voorbije drie, vier jaar zeshonderd jongeren zijn vermoord. De nationale televisiezender heeft de voorlezing van het

verdict rechtstreeks uitgezonden in het hele land. Niet alleen de

paramilitairen werden veroordeeld, maar ook de politie en het leger en

iedereen die medeplichtig is - de regering inbegrepen. De mensen uit de

buurt konden hun ogen en oren niet geloven: dat ze zelf mochten spreken in

het hart van de macht. Dat geeft toch stof tot nadenken. U zat in Brussel ook in een Irak-tribunaal. Is daar

volgens u een burgeroorlog aan de gang, of toch een godsdienstoorlog? En is

terrorisme te rechtvaardigen? HOUTART: Godsdienstoorlogen zijn zelden oorlogen waarin

het alleen over godsdienst gaat. Het religieuze element speelt een rol, maar

het is altijd complexer. Het zijn vaak hoofdzakelijk politieke oorlogen,

zoals met de katholieken en de protestanten in Noord-Ierland. Er is dus een

meer globale analyse nodig om te kijken wat er echt aan de basis van ligt.

En wat het terrorisme betreft: anderhalf, twee jaar geleden organiseerde

Fidel Castro in Havana een conferentie over terrorisme, waarop ik

uitgenodigd was. Hij was tijdens een gesprek bijzonder duidelijk. 'Geen

enkele vorm van terrorisme is geoorloofd', zei Fidel. 'Of het nu om

Palestijnen gaat, Irakezen of Tsjetsjenen.' Kortom: 'Gij zult niet doden'? HOUTART: Niet alleen dat. Er moet ook een nuance worden

aangebracht, want er is toch een verschil tussen het terrorisme van de staat

en dat van volkeren in nood. Ik herinner me dat kardinaal Oscar Romero van

El Salvador het gebruik van geweld veroordeelde, maar toch een verschil zag

tussen het geweld van de rijken en dat van de armen. Is het niet een beetje te simpel om het terrorisme van

het ene kamp als excuus te gebruiken voor het terrorisme van het andere?

HOUTART: Precies daarom moet er ook een serieuze analyse

worden gemaakt. Een groot deel van het terrorisme in het Midden-Oosten is

een gevolg van de politiek van het Westen. Wij zijn begonnen met de Taliban

en Osama Bin Laden te helpen, toen ze in Afghanistan tegen de Sovjet-Unie

vochten. Dat krijgen we nu terug. Probeert u zich ook eens in de plaats te

stellen van de mensen in Irak die met zo'n oorlog worden geconfronteerd.... Bedoelt u dat terrorisme ook een vorm van wettige

zelfverdediging kan zijn? HOUTART: Wettig nee, zelfverdediging ja. Maar ik keur

terrorisme niet goed. Al was het maar omdat het meestal het beste cadeau is

dat je de tegenstander kunt doen. 'Elf september' was voor George W. Bush

toch een geschenk op een zilveren schotel? Om zijn macht te kunnen vestigen

en zijn beleid uit te voeren? Ik herinner me een jongen in Sri Lanka. Een

Singalees, die opkwam voor de zaak van de Tamils. Hij kwam om bij een

aanslag van Tamils op een trein. Dat is het resultaat van terrorisme. Het is

politiek contraproductief. Staat het internationale terrorisme ook op de agenda

in Nairobi? HOUTART: Zolang er mensen rondlopen op aarde, zal er

terrorisme zijn. We moeten niet dromen. Maar er zal in Nairobi zeker over

worden gepraat. Hoe krijgt u in Nairobi vierduizend organisaties op

één lijn? HOUTART: Er blijven natuurlijk altijd verschillende

tendensen. Er zijn diegenen die geloven dat het kapitalisme kan worden

veranderd en er zijn diegenen die, zoals ik, denken dat het hele systeem

niet deugt. Als het forum ooit uit elkaar spat, verliezen we elke kans om

een ander Davos te maken. Dus moeten we blijven samenwerken. Tegen de

multinationals, de Wereldbank, het Internationaal Monetair Fonds. Daar zit

veel macht bij elkaar. En ik ken die mensen ook. Dat zijn geen monsters.

Maar ze leven in een andere wereld. Ik zeg hen vaak: 'Jullie zijn

analfabeten, jullie kijken alleen met een economische bril.' Daarom zijn ze

ook niet in staat om de werkelijkheid te zien zoals ze echt is. In plaats van 'Ni Marx, ni Jésus' zegt u: Marx én

Jezus? HOUTART: (lacht) Ik had daarover ooit een lang

gesprek met Michel Camdessus, die toen directeur-generaal van het IMF was.

Een praktiserende katholiek. 'Hoe komt het', vroeg ik hem, 'dat uw beleid u

zo logisch lijkt, terwijl het in Afrika en Zuid-Amerika alleen rampen

aanricht? Komt dat misschien omdat u de markt als een van God gegeven,

natuurlijk gegeven ziet?' Hij werd boos. In de markt van Camdessus spelen

sociale factoren geen rol en wegen vraag en aanbod even zwaar. Maar in de

praktijk is dat natuurlijk nooit het geval. Als de kapitalistische logica

wil spelen, móét er zelfs ongelijkheid zijn. Wie dat ontkent, vervalst het

spel. U hebt nu vijftig, zestig jaar sociale strijd achter

de rug. Is de kloof tussen arm en rijk in die tijd niet alleen maar groter

geworden? HOUTART: In algemene termen wel. Maar in Venezuela,

bijvoorbeeld, heeft Hugo Chavez het analfabetisme in korte tijd uit de

wereld geholpen. Dat is dus mogelijk. De ommekeer in Latijns-Amerika is

opmerkelijk. Ik maak mij nu vooral zorgen om de ecologische problemen. Ik

was in november in Amazonië voor een conferentie over recht en

biodiversiteit. We worden ons te langzaam bewust van wat daar gebeurt. De

vernietiging van het woud gaat in een schrikwekkend tempo voort. We kunnen de arme boeren daar toch moeilijk de

rekening voor presenteren? HOUTART: Het zijn de multinationals die het woud kappen.

De verandering van het klimaat zorgt ook voor meer schade dan het kappen

zelf. Ik durf het bijna niet te zeggen, maar er zijn onderzoekers die menen

dat er in de jaren tachtig van deze eeuw in het hele Amazonegebied geen

leven meer zal zijn. Alleen nog woestijn. En toch blijft u optimistisch? HOUTART: Cijfers over armoede in de wereld zijn geen

abstracte gegevens. Achter die cijfers gaan mensen schuil. Terwijl de

mensheid nu toch over zeven keer meer middelen beschikt dan vijftig jaar

geleden, blijft het aantal armen toenemen. Een recent rapport zegt dat als

de huidige politiek wordt aangehouden er in het jaar 2026 nog altijd 750

miljoen mensen zullen zijn die met minder dan twee dollar per dag zullen

moeten leven. Kunt u dat aanvaarden? En of de moed mij soms niet in de

schoenen zinkt? La lutte continue, quoi. Piet Piryns en Hubert Van Humbeeck

General Assembly of the United Nations

Panel on the

Financial Crisis

Francois

Houtart. Founder and President of the Centre Tricontinental and

Professor Emeritus of Sociology at the Université Catholique de Louvain.

30 October

2008

Ladies and

Gentlemen, Delegates, and Dear Friends:

The world

needs alternatives and not merely regulation. It is not enough to rearrange

the system; we need to transform it. This is a moral duty. In order to

understand why, we must adopt the point of view of the victims of this

system, Adopting this point of view will allow us to confront reality and to

express a conviction, the reality that the whole ensemble of crises which

currently afflict us -finances, food supply, water, energy, climate, social—

are the result of a common cause, and the conviction that we can change the

course of history.

Confronting

Reality

When 850

million human beings live below poverty level, and their number increases,

when every twenty-four hours tens of thousands of human being die of hunger,

when day after day entire peoples, whole cultures and ways of life simply

disappear, putting in peril humanity’s patrimony, when the climate

deteriorates to the point that one wonders whether or not it is worth the

trouble to live in New Orleans, the Sahel, the islands of the Pacific,

Central Asia, or along the coasts of our continents, we cannot content

ourselves with speaking about the financial crisis.

Already this

latter crisis has had consequences which are more than merely financial:

unemployment, rising prices, exclusion of the poor, vulnerability of the

middle classes. The list of victims grows ever longer. Let us be clear. This

crisis is not the product of some bad turn taken by one economic actor of

another, nor is it just the result of an abuse which must be punished. We

are witnessing the result of a logic which defines the economic history of

the past two centuries. From crisis to regulation and from regulation to

crisis, the unfolding of the facts always reflects the dynamics of the rate

of profit. When it rises we deregulate; when it falls we regulate, but

always in service to the accumulation of capital, which is understood as the

engine of growth. What we are seeing today is, therefore, far from new. It

is not the first crisis of the financial system and it will not be the last.

Nevertheless,

the financial bubble, created over the course of the past few decades,

thanks, among other things, to the development of new information and

communication technologies, has added fundamentally new dimensions to the

problem. The economy has become more and more virtual and differences in

income have exploded. To accelerate growth in the rate of profit, a whole

new architecture of derivatives was put in place and speculation became the

modus operandi of the economic system. The result has been a

convergence in the logic governing the disorders which characterize the

current situation.

The food

crisis is an example. The increase in food prices was not the result of

declining production, but rather of a combination of reduced stocks,

speculation, and the increased production of agrofuels. Human lives were, in

other words, subordinated to profit taking. The behavior of the Chicago

Commodity Exchange demonstrates this.

The energy

crisis, meanwhile, goes well beyond a conjunctural explosion in the price of

petroleum. It marks the end of cheap fossil fuels, which encouraged

profligate use of energy, making possible accelerated economic growth and

the rapid accumulation of capital in the middle term. The superexploitation

of natural resources and the liberalization of trade, especially since the

1970s, expanded the transport of commodities around the world and encouraged

the use of automobiles rather than public transportation, without

consideration of either the climatic or the social consequences. The use of

petroleum derivatives as fertilizers became widespread in a productivist

agriculture. The lifestyle of the upper and middle classes was built on this

squandering of energy resources. In this domain as well exchange value took

precedence over use value.

Today, with

this crisis threatening gravely the accumulation of capital, there is a

sudden urgency about finding solutions. They will, however, respect the

underlying logic of the system: to maintain the rate of profit, without

taking into account externalities -that is to say what does not enter into

the accounting of capital and the cost of which must be born by individuals

and communities. That is the case with agrofuels and their ecological and

social consequences: destruction by monoculture of biodiversity, of the soil

and of underground water and the expulsion of millions of small peasants who

then go on to populate the shantytowns and aggravate the pressures to

emigrate.

The climate

crisis, the gravity of which global public opinion has yet to take the full

measure, is, according to the International Group of Climate Experts, the

result of human activity. Nicolas Stern, formerly of the World Bank, does

not hesitate to say that “climate change is the biggest setback in the

history of the market economy.” In effect, here as before, the logic of

capital does not taken into account “externalities” except when it reduces

the rate of profit.

The neoliberal era, which led to the increase of the later, coincided as

well with growing emissions of greenhouse gases and accelerated global

warming. The growth in the utilization of raw materials and in

transportation, as well as deregulation in the ecological sphere, augmented

the devastation of our climate and diminished the regenerative capacity of

nature. If nothing is done in the near future, 20%-30% of all living species

could disappear in the next quarter century. The acidity of the oceans is

rising and we can expect between 150 and 200 million climate refugees by the

middle of this century.

It is in this context that we must understand the social crisis. Developing

spectacularly the 20% of the world’s population capable of consuming high

value added goods and services, is more interesting from the standpoint of

private accumulation in the short and middle term than responding to the

basic needs of those whose purchasing power has been reduced to nothing.

Indeed, incapable of producing value added and having only a feeble capacity

to consume, they are nothing but a useless mob, or at best the of object

welfare policies. This phenomenon is accentuated with the predominance of

finance capital. Once more the logic of accumulation has prevailed over the

needs of human beings.

This whole ensemble of malfunctions opens up the possibility of a crisis of

civilization and the risk that the planet itself will be purged of living

things, something which also signifies a real crisis of meaning. Regulation,

then? Yes, if they constitute steps towards a radical and permanent

transformation and point towards an exit from the crisis other than war. No,

if they merely prolong a logic which is destructive of life. A humanity

which renounces reason and abandons ethics loses the right to exist.

A conviction

To be sure, apocalyptic language is by itself a sufficient catalyst for

action. On the contrary, a radical confrontation with reality like that

suggested above can lead to reaction. Finding and acting on alternatives is

possible, but not without conditions. It presupposes a long term vision, a

necessary utopia, concrete measures spaced out over time, and social actors

who can carry these projects and who are capable of carrying on a struggle

the violence of which will be proportional to the resistance to change.

This long term vision can be articulated along several major axes. In the

first place, a rational and renewable use of natural resources, which

presupposes a new understanding of our relationship with nature: no longer

an exploitation without limits of matter, with the aim of unlimited profits,

but rather a respect for what forms the very source of life. “Actually

existing” socialist societies made no real innovations in this domain.

Second, we will privilege use value over exchange value, something which

implies a new understanding of economics, no longer as the science of

producing value added as a way of encouraging private accumulation but

rather as an activity which assures the basis for human life, material,

cultural, and spiritual, for everyone everywhere. The logical consequences

of this change are considerable. From this moment forward, the market must

serve as a regulator between supply and demand instead of increasing the

rate of profit for a minority. The squandering of raw materials and of

energy, the destruction of biodiversity and of the atmosphere, are combated

by taking into account ecological and social “externalities.” The logic

governing the production of goods and services must change.

Finally, the principle of multiculturalism must complement these others. It

is a question of permitting all forms of knowledge, including traditional

forms, all philosophies and cultures, all moral and spiritual forces capable

of promoting the necessary ethic, to participate in the construction of

alternatives, in breaking the monopoly of westernization. Among the

religions, the wisdom of Hinduism in relationship to nature, the compassion

of Buddhism in human relations, the permanent quest for utopia in Judaism,

the thirst for justice which defines the prophetic current in Islam, the

emancipatory power of the theology of liberation in Christianity, the

respect for the sources of life in the concept of the land itself among the

indigenous peoples of the Americas, the sense of solidarity expressed in the

religions of Africa, can all make important contributions in the context of

mutual tolerance guaranteed by the impartiality of political society.

All of this is utopian, to be sure. But the world needs utopias, on the

condition that they have concrete, practical results. Each of the principles

evoked above is susceptible to concrete applications which have already been

the object of propositions on the part of numerous social movements and

political organizations. A new relationship with nature means, among other

things, the recovery by states of their sovereignty over their natural

resources and an end to their private appropriation, the end of monocultures

and a revaluation of peasant agriculture, and the ratification and deepening

of the measures called for by the Kyoto and Bali protocols on climate

change.

Privileging use value requires the decommodification of the indispensible

elements of life: seeds, water, health, and education, the re-establishment

of public services, the abolition of tax havens, the suppression of banking

secrecy, the cancelation of the odious debts of the States of the global

South, the establishment of regional alliances on the basis not of

competition by of complementarity and solidarity, the creation or regional

currencies, the establishment of multipolarity, and many other measures as

well. The financial crisis simply gives us a unique opportunity to apply

these measures.

Democratizing societies begins with fostering local participation, includes

the democratic management of the economy, and extends to the reform of the

United Nations. Multiculturalism means the abolition of patents on

knowledge, the liberation of science from the stranglehold of economic

power, the suppression of monopolies on information and the establishment of

religious liberty.

But who will carry this project? The genius of capitalism is to transform

its own contradictions into opportunities. How global warming can make

you wealthy! reads an ad in US Today from the beginning of 2026.

Can capitalism renounce its own principles?

Obviously not. Only a new set of power

relations can get us where we need to be, something which does not exclude

the engagement of some contemporary economic actors. But one thing is clear:

the new historic actor which will carry the alternative projects outlined

above is plural. There are the workers, the landless peasants, the

indigenous peoples, women (who are always the first victims of

privatization) the urban poor, environmentalists, migrants, and

intellectuals linked to social movements. Their consciousness of being a

collective actor is beginning to emerge. The convergence of their

organizations is only in its early stages. Real political relationships are

often lacking. Some states, notably in Latin America, have already created

the conditions for these alternative projects to see the light of day. The

duration and intensity of the struggles to come depends on the rigidity of

the system in place and the intransigence of the protagonists.

Offer them, therefore, a platform in the General Assembly of the United

Nations, where they can express themselves and present their alternatives.

This will be your contribution to changing the course of history -something

which is must happen if humanity is to recover the space to live and

once again find reason to hope in the future.

PORTRAYING THE PERSON AND THE WORK OF FRANCOIS

HOUTART

Based on Interviews in July 2026 in

Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium

JEROME

SAHABANDHU Abstract

This report

that compiled in a question-answer format contains the first

of an interview series I have conducted with Prof. François

Houtart of Belgium

as a part of an ongoing research.

Interview sessions were conducted in

July 2026 at the Tri-Continental Centre in

BACKGROUND to François Houtart

Houtart was born in

Brussels in 1925.The young seminarian completed his Philosophy and

Theology in Malines, Belgium in 1949.His initial experiential

context was in the aftermath of World War II (1939-1945).

Houtart, as a student encountered one of the very crucial social

issues at that time, namely, the sitz im leben of the working

class community, in particular of the young workers and wanted

urgently to respond to the issue. This led him to study sociology of

religion.

Houtart obtained a

Licentiate in Socio-Political Sciences from the Catholic University

of Louvain (KUL) in 1952. Upon completion of a postgraduate course

in Urban Sociology at

In 1956, Houtart

founded the Center for Socio-Religious Research (CSRR) and in the

same year became the secretary general of the International

Conference of Sociology of Religion. After 1958, he directed various

research projects and empirical studies for the International

Federation of Institutions for Socio-religious and Social Research (FERES).

Responding to Third

World issues together with the purpose of convergence and solidarity

of the social movements, specifically those occurring in the

southern hemisphere, Houtart founded CETRI- centre tri-continental

in Louvain-la-Neuve in 1976. The third World Documentation Centre of

CETRI is now integrated to the UCL library, Louvain-la-Neuve.

Houtart has carried out socio-religious research

in various countries, such as

Some of the theological

colleges and institutes in South India and

In

1996, at the twentieth anniversary of CETRI, Houtart proposed a

meeting that later became the “Other Davos”, with the view of

creating a counter movement to the dominant world economic forum in

Davos in 1999. The World Forum for Alternatives came into being, as

a result and paved the way to the World Social Forum (WSF) in Port

Alegre in 2026. Houtart was one of the co-founders of the WSF.

Houtart was the Chief

Editor of the international journal Social Compass from

1960-1999. He served on the advisory council of the Catholic Journal

Concilium while contributing to the pages. A quarterly from

Houtart is actively

involved in the Brussels Tribunal for the war in

THE INTERVIEW

Q: What have been the most

important stages and turning points in your priestly and

intellectual life?

A: In the late

forties I was very conscious of the situation of the

working class

community. My experiences with the

Young Christian Workers (YCW) challenged me a lot. Josef Cardijn was

an inspiration for me. He was the founder of the Young Christian

Workers Movement and later became a Cardinal. The situation of young

workers at that time was extremely difficult. The working class went

through a very difficult time during and after the Second World War.

After my ordination in 1949 I asked

permission to proceed with studies in the social sciences. I studied

the religious situation of cities: in particular,

I did a similar kind of study in

This research work was an important turning point

for me - in order to better study the pastoral issues of the working

class I opted for a sociological approach.

The second turning

point was my travels in

My

first visit in Latin America was in

In Brazil I had worked with Dom Helder Camara,

who later became the Vice-President of the Bishops’ Council of Latin

America (CELAM), so when the Council was announced he asked me to

make a synopsis (résumé) of my research in Latin America to

distribute to all the Bishops at the beginning of the Council so

they might better understand the Latin American situation. I was

then appointed as an expert to the Latin American Bishops.

The third turning point

was my commitment against the war in Vietnam.

My work in

Of course, I had already been involved with the

struggles in

It was my experience in Latin America, which led

me to discover the context of

Later, I became the Chairperson of the

Belgium-Vietnam Association and was invited to

Another important

turning point has been

Because my Latin American work had reached a

certain stage, after Vatican II, where I had also been involved with

Gaudium et Spes, the secretary of the sub-commission of Latin